- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

A Family Apart Page 8

A Family Apart Read online

Page 8

Frances quickly shook her head. “We don’t have to talk about it.”

“But I want to, because it’s my fault that all the rest of you are here, and I’m sorry I did this to you.”

“Oh, Mike.” Frances reached out to touch her brother’s hand. “I don’t blame you.” She tried to make her voice light. “Look at it this way. You kept telling me I’d like living in the West. Now I’ll have a chance to find out.”

But Mike didn’t respond to her attempt at humor. “This is our last time to be together. After we’re placed, who knows when we’ll see each other again?”

“We may not know when we’ll be together again, but I’m sure that we will be. I’ll write to you. Will you write back?”

Mike nodded. “Sure. And someday—”

But the train squealed to such a sudden stop that they were thrown off-balance.

“Outlaws!” a woman screamed as a heavily bearded man burst through the door to their car, waving a rifle at the passengers.

Shrieks and yells came from the other cars as men on horseback galloped at each side of the train. One of the men reined in his horse and poked a long gun in through one of the open windows of the children’s car.

The bearded man waved a small cloth sack at the passengers. “Sit down right now! All of you! And don’t do anything we don’t tell you to do,” he snapped.

As she dropped back onto the bench, Frances saw Captain Taylor glance at the man on horseback outside the window and back to the outlaw in the aisle. She held her breath, wondering what he would do. But he sat quietly and kept his hand away from his satchel and his gun.

“Everybody pay attention,” the outlaw demanded, little drops of spittle glittering on his beard. “Put your money and valuables in this sack.” When they were slow to react he yelled, “Now!” and jabbed the end of his rifle at Mr. Crandon’s stomach.

“Don’t do that!” Mr. Crandon squeaked. “I’ll give you all my money! See! Here it is!” He fumbled for a wad of bills held with a gleaming gold money clip and dropped it into the sack.

The outlaw moved up the aisle, thrusting the open sack ahead of him, his nervous eyes darting from one passenger to another. One by one the passengers obeyed as the outlaw eyed them closely. The women even stripped off their rings and bracelets and dropped them into the sack, and some of the men gave up their pocket watches.

As the outlaw came to Katherine she said, “I have no money.”

He glanced at her hand. “You have a ring. Take it off.”

“Oh, please let me keep it!” Katherine said. Frances was amazed to see tears in her eyes. “It’s not of much value, but it means a great deal to me.”

The man quickly glanced at the man on horseback, then back at Katherine, and his voice grew even more loud and harsh. “You heard me! Drop it in the sack! Now!”

As Katherine obeyed, the outlaw outside the window called, “Get a move on! We’re ready to ride!”

Cautiously, his gun held before him, the bearded outlaw began to back away from the passengers. Suddenly Mike was in the aisle, plowing into the man, and they stumbled together as the cloth bag was almost jerked from the outlaw’s hand. Angrily the man regained his balance, giving Mike such a hard clout with his left hand that he knocked him sprawling. Mike bounced off the edge of the nearest seat and landed on the floor of the car, curled facedown, not moving.

Frances gasped and rushed toward Mike as the outlaw jumped from the car. She could hear more yelling and the sound of galloping horses as he and the rest of his gang raced away from the train. The sound of gunshots exploded outside the window, and Captain Taylor shouted, “Got one of them! But just in the shoulder, blast it!”

“Mike! Wake up!” Frances begged as she threw her arms around him. Danny dove in next to her, and in the next minute Andrew and Katherine were beside her, ready to help. But Mike squirmed away from Frances, struggled to his knees, and stood up, one fist clenched against his chest.

Frances scrambled to her feet, too, trying once more to put her arms around her brother. “Oh, Mike! Are you hurt?”

Mike pulled away to face all the other staring passengers. Frances could see him try to smile, but tears filled his eyes.

“I was a copper stealer once.” Mike’s voice was barely a whisper. “I promised Ma and I promised myself that I would never pick pockets again, but I couldn’t let that outlaw take Mrs. Banks’s ring, not when it meant so much to her.”

He held out his fist and dropped the ring into Katherine’s hand.

“Oh!” Katherine gasped. “Oh, Mike!” She held the ring up to stare at it as though she couldn’t believe it was really there, and tears came to her eyes, too. Quickly she bent to wrap Mike in a hug.

Around them people murmured, “How did he manage that?” “What did that boy do?”

“There’s more,” Mike mumbled against Katherine’s shoulder. When she stepped back he held out his hand, palm up, and opened his fingers. In it lay a wad of bills. As everyone stared, Mike gave the lot to Andrew. “I couldn’t get it all,” he apologized, “but maybe those who lost their money could divide this.”

“Good, good!” Mr. Crandon stretched to see, then scowled. “What’s this! What about me? He didn’t retrieve my gold money clip!”

One of the women began to chirp like a frightened bird. “The bag will be almost empty! What if that outlaw notices and comes back?”

Mike shook his head. “He won’t notice. I dropped my book in the bag to give it weight.” He managed a shaky grin. “The tales in those novels about brave, daring outlaws are wrong. There wasn’t anything grand about that man. He was dirty and fat and smelled like a New York gutter in summer.’ ”

Katherine put an arm around Mike’s shoulders, hugging him again. “You risked your life!” she said. “You shouldn’t have done that.” As Mike ducked his head Katherine slipped the ring back onto her finger and added quickly, “But oh, Mike, my friend, I thank you with all my heart for retrieving my ring.”

Captain Taylor stepped forward to shake Mike’s hand. “You exhibited great courage,” he said. “I’m proud of you.”

Mr. Crandon’s booming voice almost drowned out the captain’s words. “You all heard that boy. He admitted to being a copper stealer, a common pickpocket!”

“Just a minute, Mr. Crandon!” Katherine said. “This is the boy who saved your life during the fire.”

But Mr. Crandon sputtered, “Saved my life? That’s debatable! All I know is that he ruined my trousers!”

“You’re not being fair to Mike! He risked his life with that outlaw to try to save some of our property.”

“He tried to help!” Danny echoed as he stepped in front of Mike.

Mr. Crandon wrinkled his nose as though he’d just smelled something bad. “Granted, the boy thought he was doing right,” he said. “I’ll give you that much. But don’t you see? It simply proves my point. He’s never learned the right values.”

“That’s not true!” Frances exclaimed, but Mr. Crandon ignored her.

“A boy like that should not be allowed in a proper home! And I’ll do my best to see to it that he isn’t!”

“Mr. Crandon—” Andrew began.

But a woman who had boarded the train at Hannibal raised her voice to shout over his. “I agree. Perhaps the boy could be sent back to New York.”

Her companion clutched the lapels of her jacket together as though Mike had plans to steal it and stammered, “I think Mr. Crandon should take steps to see this is done. We don’t need a New York pickpocket here!”

“No!” Frances could stay quiet no longer. She stepped in front of Mike and faced the surprised passengers.

“In New York,” she said, “we worked very hard, but we didn’t always have enough to eat. And we didn’t have clean, fine clothes like those we’re wearing now. And we didn’t have our father. Da died last year. Mike was wrong to steal, but he thought he had to so that he could bring home a bit of meat now and then. He tried in his own way to

help.”

She took a long breath and hurried on before she could lose what little courage she had left. “We’re people just like you, who have the same feelings you have.”

The woman who earlier had spoken up for the children held out a hand, as though she were reaching for Frances, and said, “Oh, my dear child, it’s plain that some of us have forgotten that you had no parents to guide you.”

“We have a parent. We have a mother,” Frances said, “and she and Da taught us, over and over again, the rules we should follow.”

“You have a mother? But where is she?”

Frances held her chin up, willing it to stop trembling. “She sent us west,” she said, trying to repeat Ma’s words without thinking about them, “because she wanted us to have better lives than she could give us.”

Without another word the passengers drifted back to their seats. The children, subdued and silent now, sat clustered together on the benches.

Andrew squeezed into the seat next to Frances. “Well spoken, son,” he said. “I think you and Mike will do very well for yourselves in the West.”

Frances glanced back at Mr. Crandon. She couldn’t help being afraid, not just for Mike, but for all of them. Every minute was taking them closer to St. Joseph, to the place she had never seen that might be her home for the rest of her life. What would happen to them then?

8

EARLY IN THE morning, as they approached the town of St. Joseph, Frances wistfully watched Katherine busy herself with brushing and braiding the girls’ long hair. From under a seat Katherine pulled a small valise and began extracting fresh hair bows from it as though she were a magician.

Katherine smoothed and straightened dresses, tidied jackets, and made sure that all buttons were buttoned. Frances brushed off her own jacket with trembling fingers.

“You look wonderful,” Katherine said. “The people who come to meet you will be impressed.”

For a moment the children were quiet, then Danny spoke up. “What if no one comes?”

Katherine laughed, and Andrew seemed surprised. He motioned toward the windows. “Have none of you looked outside?”

Frances quickly turned toward the nearest window and was shocked to see a number of people in buggies or wagons, driving in the same direction as the train on a road parallel to the tracks. They were not dressed as elegantly as the people in New York. There were no top hats or canes to be seen among the men, and the women—many of whom wore broad-brimmed hats to shield their faces from the sun—were wrapped in shawls rather than elegant woolen coats. As Frances and the other children on the train stared at them, the people smiled and waved eagerly.

“Are they coming to see us?” Peg’s voice was a squeak.

“Yes, and many more with them,” Andrew said.

“All those people! How did they know we were coming?” a boy asked.

“Letting them know about you was part of my job,” Andrew explained. “I put an advertisement in the St. Joseph Weekly West that told about the society’s placing-out program. We received a response immediately, so I set up a committee of three prominent St. Joseph citizens to approve applicants. The next step was to bring you to St. Joe.”

“Will we all live in St. Joseph?” someone asked.

“No. Most of you will live on nearby farms. A few of you will probably be adopted by families who live across the Missouri River in the Kansas Territory. And because we’re so close to the borders of Iowa and Nebraska Territory, some of you might even find homes with families there.”

Frances could feel the shudder that ran through Megan’s body as she squeezed close and held tightly to Frances’s hand. She heard Danny murmur again, “You and me together, Mike. Right?”

Curiosity and excitement overcame Frances’s fear. She pressed against the car window to see the busy, noisy town. Horseback riders, wagons, and foot traffic crowded the streets, just as they did in New York. But in St. Joseph, the streets were dirt, and few of the buildings were higher than two stories. The other children pushed to the windows, pointing and yelling as the train chugged into the station and rattled to a stop.

Many of the passengers on their car paused before leaving to say good-bye to the children and wish them well.

Captain Taylor came to where Frances stood with Mike and solemnly shook hands with both of them. He turned toward Mike. “Remember that the West is a place for new beginnings. You may think that you sacrificed your reputation, but you did not. It’s what you make of your future that will count. And I believe that you’ll have a good future, because you’re a fine young man.”

Mike blinked in surprise. “No one’s called me a fine young man since my father died.”

“Then it’s time they did,” Captain Taylor said. He placed a firm hand on Mike’s shoulder. “I hope I will see you again. If either of you boys ever wants to get in touch with me, remember that I’ll be at Fort Leavenworth, which is on the Kansas side of the Missouri River, about a day’s ride south of St. Joseph.”

“Thank you, sir,” Mike said, and Frances nodded.

She and Mike stood silently for a moment, watching the captain leave the car. The station was a confusion of passengers, porters, and freight. Frances wished she could shrink back and disappear. She wondered if Mike were as frightened as she was.

“All right, children,” Andrew called as soon as the adult passengers had left the railcar. “Let’s get up here and form a line. We’ll walk together over to one of the churches where people will come to meet you.”

Holding tightly to Petey’s hand as he managed the steep steps from the railroad car, Frances paused to look around the station. People were crowded on the platform in front of the small wooden building that served as a depot. Many of them were smiling. A few waved at the children. But here and there she saw someone appraising them the way Ma sometimes studied the greengrocer’s cabbages. Which was the roundest, the heaviest? Which was the best?

Katherine turned to the children. “There’s Jeff Thompson.” She quickly corrected herself. “Mr. Merriweather Jeff Thompson, that is. He’s the mayor of St. Joseph, elected just last year.”

The mayor beamed at the children and began a speech of welcome. Frances was so distracted she only heard bits and pieces of the speech. “… the fine work of the Children’s Aid Society … the good, upstanding people who are making a sacrifice to—”

Sacrifice? Frances thought. That’s the word Ma had used. Her mother’s sacrifice had been to give her children away, while these people’s sacrifice was to keep them. Frances didn’t understand it.

The mayor had just finished thanking Andrew and Katherine for their part in the undertaking when he was interrupted by the shouts of a short, thin boy dressed in a leather jacket and breeches. A wide-brimmed felt hat was pulled down on his head, the front of the brim fastened so that it stood straight up. Frances guessed that he was no older than fifteen or sixteen. He shoved his way through the crowd, holding aloft empty leather saddlebags and shouting importantly, “Make way!”

Mr. Thompson looked surprised for just an instant. Then he said to the crowd, “Make a path for Billy Cody. The pony express must go through.”

“Pony express! The mail to California!” Mike whistled through his teeth and pointed to a poster that was nailed on a nearby post:

WANTED: Young Skinny Wiry Fellows, not over

eighteen. Must be expert riders willing to

risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages

$25 per week. Apply Central Overland Express.

“I could learn to ride,” Mike said.

A man standing close by smiled and said, “It would take a while of practice and a great deal of skill to ride like Bill Cody and the other pony express riders.”

Bill Cody ran from the depot, his saddlebags bulging with mail, and Frances could see him toss them over a stocky, saddled pony that was tied to a hitching rail. He leapt across the pony’s back and galloped out of sight.

Andrew and Katherine shepherde

d the children into line and began their march to the church. Most of the adults in the crowd joined the walk, falling into line behind the children. A few curious town boys darted in to stare, sometimes pointing and snickering.

“We could take them on,” Danny muttered to Mike, but Frances, with a warning scowl, pulled him back into line.

“They’re of no account,” she said, as though her feelings hadn’t been hurt by the taunts. “We’ve got more important things to tend to.”

The wooden sidewalks clattered under their feet, and as they crossed the streets, the women—most of whom, Frances noted, were dressed in dark homespun—held up their skirts to keep them out of the dust, stepping carefully over deep wagon ruts and horse droppings. Breaking the mingled odors of sweat and leather and dust were the gusts of a breeze that carried the damp, pungent fragrance of river water and wet grasses.

There was so much to see that Frances kept looking from side to side, occasionally stumbling: Indians, wrapped in blankets; men called frontiersmen, as brown as their deerskin jackets and leggings; people on horseback; even a team of oxen pulling a huge, canvas-covered wagon, pans and tools dangling from each side. At the western end of the street, Frances could see the glimmering water of the Missouri River, crowded with boats of all sizes.

The parade of children turned another corner and came to a large wooden building, which was painted white and topped by a steeple and cross. Andrew opened wide the double doors, and Katherine led the children to a raised platform at the far end of the room. A piano and stool were at one end, a carved, dark-stained pulpit at the other, and a deep red curtain hung over the back wall. Two rows of wooden chairs had been placed across the platform to face the room.

“Please find a seat on one of the chairs,” Katherine directed.

Frances, terrified that Petey and she would be separated, held him on her lap and wrapped her arms protectively around him.

To Frances’s right sat Peg, then Danny, who inched his chair closer to Mike’s. Mike sat stiffly, his face so pale with fear that his freckles stood out like blots of splattered ink. Frances wished she could comfort him—Megan, too, who was on her left, her knuckles bone-white as she gripped the edge of the wooden seat—but Frances was so frightened she was unable to think of what to do.

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

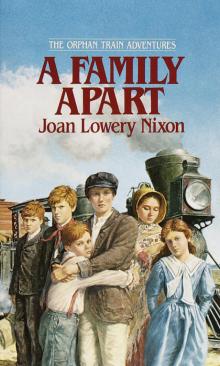

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island