- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Read online

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

For Katherine Joan McGowan with my love.

p

A Note From the Author

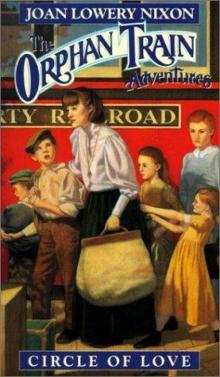

During the years from 1854 to 1929, the Children's Aid Society, founded by Charles Loring Brace, sent more than 100,000 children on orphan trains from the slums of New York City to new homes in the West. This placing-out program was so successful that other groups, such as the New York Foundling Hospital, followed the example.

The Orphan Train Adventures were inspired by the true stories of these children; but the characters in the series, their adventures, and the dates of their arrival are entirely fictional. We chose St. Joseph, Missouri, between the years 1860 and 1880 as our setting in order to place our characters in one of the most exciting periods of American history. As for the historical figures who enter these stories—they very well could have been at the places described at the proper times to touch the lives of the children who came west on the orphan trains.

Vcr«^^^v*x^ yOy

wiflut

Aauiabcrofthe CHILDREN brought from IfEW YORK ara etlll without homes.

,T.

SEE TMBWL

1ER6HANTS, FARMERS

AND FRIENDS GENERALLY ft T« req'aaeted to give publicity to the above

H. iiklEDGEN Agent

'Tinished!" Jennifer put the last dish away in the cupboard and quickly turned toward her grandmother. "You promised to read to us from Frances Mary's journal as soon as the kitchen was in order."

"It looks good to me," her brother, Jeff, said. Hoping that Grandma wasn't watching, he brushed a few stray toast crumbs from the kitchen counter into his hand and stuck his hand in the pocket of his jeans.

Grandma winked at Jeff. "The kitchen looks good to me too—especially that very clean counter." She held up the book, which was covered in faded blue fabric, and said, "I have the journal right here, so why don't we settle down on the screened porch, and read about the Kelly family's next adventure?"

Jennifer and Jeff raced to see who could get to the porch first. Jennifer curled up on the cushions of one

of the wicker chairs and squirmed with anticipation as Grandma opened the book to Frances's delicate, spidery handwTiting.

"Frances Mary dated this entry, 'Autumn of 1863,' " Grandma said.

"Was the Civil War over then?" Jeff asked.

"No," Grandma said. "The War Between the States had escalated. In January of 1863 President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all slaves in Confederate states, and the bitterness and anger increased."

Surprised, Jeff said, "But that was two years after the war started. I thought that freeing the slaves was what the war was all about."

"Last year in history class Mr. Wilson told us that the main reason for the war was economic," Jennifer said. "The northern states wanted to put a stop to slavery in the United States, but the people in the southern states said their economy would collapse without slave labor. They seceded from the Union so they could form their own country, and they fired the first shots, which began the war."

Wishing that Jennifer weren't always such a know-it-all, Jeff grumbled, "Okay, okay. Let Grandma get started. I want to hear more of Frances's story."

"So do 1," Jennifer said. She settled back as Grandma began to read:

No one who has not been touched by the devastation of war could possibly understand its horrors. With some commanders and their troops it is not enough to win a battle or lay claim to strategic areas. People like Confederate William Quantrill and his raiders seem to take great satisfaction in

terrorizing entire villages by stealing, burning, and destroying homes and stores and — even worse — randomly killing all males who favor the Union, including young boys and elderly men.

During the fourth week of August we gave shelter to a badly frightened woman, who had escaped QuantrilVs murderous sack of the town of Lawrence by fleeing northward. It was the mercy of Providence that led her to our quiet farm community and to our home. In spite of the kindness and reassurance shown her by the Cummingses, Violet Hennessey—for that was her name — was so shaken and fearful that for days she could not abide to be left alone.

"/ cannot remain in Kansas, " Violet told us. "I want to go home to Boston. "

"Travel at this time will be very difficult, " Mrs. Cummings told her, but Violet was insistent.

'Tve heard there are still trains able to leave St. Joseph for the East," she said. She seemed intent — almost stubborn.

''St. Joseph, like all of Missouri, is in turmoil."

''But the area in and around St. Joseph has been spared the violent attacks from jayhawkers and bushwhackers that have plagued the counties along the border farther south. Frances, you told me yourself that your family members who live in and near St. Joseph have remained free from harm. "

Violet's thoughtful, deliberate words were in vivid contrast to her ordinary manner. As soon as she had finished speaking, she pulled her shawl more tightly around her shoulders, her sad little face poking out like a wary swamp turtle's. "If I can get to St. Joseph, " she said, "somehow, some-

where, Fll find a safe place in which to stay until Fm strong enough to travel. "

A safe place in St. Joe.

Immediately, I thought of Ma.

Peg Kelly closed her eyes and inhaled the warm cinnamon-sugar smells of the kitchen. Nibbling, she held a tiny bite of apple dumpling on her tongue to make the birthday treat last longer.

Her mother smiled and winked. "You needn't be afraid to gobble it down. There'll be more dumplings with supper tonight."

Peg gulped and dipped her spoon into the flaky pastry for another bite. "You're a good cook, Ma."

"And you're a good daughter, little love."

"I am not little. I'm eleven now." Peg sat up defensively and squared her shoulders, as though she could will herself to add an inch or two to her height of four feet, eight inches. "I'm practically grown."

Noreen Kelly Murphy added wood to the fire in the cast iron cookstove, then picked up a heavy pan,

which contained a fat hen, stuffed almost to bursting with a mixture of bread crumbs, minced onion, and herbs.

Peg's eyes gleamed. "Roast chicken, too! Oh, yimi!" It wasn't often they were able to have meat. Both the Confederate and Union raiding parties helped themselves to farmers' stock and food supplies. There was precious little left for the stores to sell.

As Ma tucked the chicken inside the oven. Peg heard the creak of buggy wheels and the clop of horses' hooves stop in the road outside their house.

"Someone come to visit?" Ma asked and held aside the lacy curtain that hving over the kitchen window. "Oh, merciful heavens!" she cried in delight. "It's Frances Mary!"

Peg threw down her spoon and raced to the door, flinging it open and screeching, "Frances! Frances!" She wrapped herself in her big sister's hugs.

Frances turned to greet Ma, who held her tightly. Over Frances's laughter Ma chattered on. "It's been months since I've laid eyes on you, Frances Mary! And look at you! Blooming with good health, praise be! How is my Petey? Did you bring him with you this time? He's well, isn't he?" She craned her neck, staring toward the wagon.

"He's fine. Ma. I'm fine. And so are the Cum-mingses."

Ma abruptly stopped speaking. In surprise. Peg followed her mother's gaze and saw a woman standing beside the wagon. She was pale, her skin nearly matching the faded gray of her cotton dress and bonnet. Almost apologetically she hung back, and when she met Peg's glance, she smiled shyly and ducked her head.

Frances, one arm still around her mother, turned

toward the woman. "Ma, . . . Peg," she said, "I want you to meet Violet Hennessey. Miss Henne

ssey fled from her home in Lawrence, when Quantrill and his raiders burned the town. She needs a place to stay for a short while, Ma, so I brought her to you."

"And rightly so," Ma said without hesitation. She immediately took charge, sending Peg to plump the pillows on the bed in the spare room and fill the pitcher with fresh water.

By the time Peg returned to the kitchen, Frances had left to stable the horse, and Ma had ushered Miss Hermessey into a chair by the fireplace.

A cup of tea already in her trembling hands, Miss Hermessey murmured, "It will be just for a few days. Just until I can find suitable lodgings."

"We're happy to have you stay with us," Ma reassured her. She pulled up a chair facing Miss Hermessey. "Here in St. Joe we heard about Quantrill's attack on Lawrence. It must have been terrifying."

Eager to hear any details that Miss Hennessey might offer. Peg took a step forward. She realized her mistake when Ma immediately spotted her.

"Miss Hermessey's two carpetbags are on the fioor by the door," she said. "Will you please take them to her room. Peg, my girl? One at a time now, because they're heavy."

"But, Ma, I want to hear about the raid."

"Now, please," Ma said firmly.

To argue in front of a guest was imthinkable, so Peg silently turned and did as she had been told, but inside she fumed. She sent me off on purpose so I wouldn't hear. She treats me as ifPm a child. And I'm not! Fm close to becoming a full-grown woman!

The first bag wasn't particularly heavy, but Peg lugged the second bag up the stairs with difficulty. It

was more scuffed than the first one, the flocking worn and stained at the comers. How did Miss Hennessey escape quickly if she had to carry these two bags? Peg wondered, then shrugged.

By the time Peg returned to the kitchen Frances had joined Ma and Miss Hennessey, who was now spooning up a bowl of chicken broth.

Peg glanced wistfully toward the apple dumpling she had left. Her mouth watered for it, but it would be rude to eat it if Miss Hennessey had not been served some, and she would rather wait than give up any of her own portion at the moment.

"And your friend, Johnny?" Ma was asking Frances. "Is he also well?"

Frances's cheeks suddenly turned pink, and she stared down at her cup of tea. "He writes when he can," she said. "He's with the Kansas Volunteers."

"He's in my prayers, love, along with all the other young men who have gone off to fight." Ma patted Frances's shoulder.

"On the Union side," Peg said and pulled up a chair.

"On both sides," Ma corrected.

"Ma!" Peg was shocked. "You can't pray for the Confederates!"

"I'm praying for all the boys who have left their homes to fight for what they believe in, no matter if they're right or wrong," Ma said. "They all have mothers who lie awake at night worrying about them."

"But we're under martial law. The provost marshal arrests anyone who helps the enemy in any way."

Ma laughed. "Fortunately, the provost marshal has no way of knowing what's in my mind and heart."

Frances smiled and reached over to hug Peg. "Let

Ma be," she said. "Today's your birthday, and I didn't forget. I brought you a bag of molasses taffy."

"Yum!" Peg said, but at that moment Miss Hennessey gave a little moan and swayed in her chair.

Ma and Frances jumped to their feet. Ma clutching Miss Hennessey's shoulders to keep her from falling.

"I'm sorry." Miss Hennessey's voice was so faint she could scarcely be heard. "Maybe it was the long journey. I'm so tired ... so tired."

"Then it's bed for you," Ma said. "A good sleep may be all that you need. Don't even think of coming down to supper. I'll bring up a tray."

"Thank you," Miss Hennessey whispered. With Ma's help she rose from her chair and stimnbled from the room, supported by both Ma and Frances.

Quick as a shot Peg snatched her half-eaten apple dumpling and began to gobble it down. It was no longer warm, and the cream had soaked through the lower crust, but it was still delicious.

In a few minutes Ma and Frances came downstairs, pausing at the foot of the staircase to talk in low tones.

Peg felt a lump in her throat as she watched her sister, whose dark, shining hair gleamed in a beam of late afternoon sunlight that came from the fanlight window over the front door. Frances had grown taller and even more beautiful. With her small waist and rounded breasts and hips, at sixteen she had become a lovely woman.

Peg slid her hands over her own flat chest and grimaced. She wanted to look like Frances, to be as kind and loving as Frances, and to be as brave as Frances had been when she risked her life to work with the Underground Railroad, helping slaves to escape to freedom.

Besides, she thought, as she licked the last drop of

cream from her bowl, by the time Fm sixteen maybe Ma will stop treating me like a child!

Supper preparations soon began, and Peg helped by cutting pole beans into a pot for boiling and setting the table.

Her stepfather, John Murphy, arrived home from his blacksmith's shop. The shirt that stretched over his broad shoulders was stained with sweat. He greeted Frances warmly and raised his thick black eyebrows in surprise when told of their guest.

"Were you acquainted with this woman before the raid?" he asked Frances.

"No," she answered.

"Then how did she happen to go to the Cimi-mingses for help?"

"Pure fortime," Frances said. "She was on the road after dark and spotted the lights in our house. She knocked on our door and asked us to take her in."

"Who are her people? Where is she from?"

"That I can't tell you. I simply know that Miss Hennessey is frightened and alone. She wanted to leave Kansas, and I thought that Ma ..."

"Your ma. Ah, yes indeed," Mr. Murphy said with a frown. "She's very good at taking in strays, without thinking of the consequences. Just between you and us and no one else, last week Noreen risked arrest by feeding a Union Army deserter who stopped and asked for food."

Indignant, Ma thrust both hands onto her hips. "It's not up to me to be judge and jury, John Murphy. All I saw was a frightened, hungry boy—of no more than sixteen years of age, if that much—curled up under the washtub in our backyard, trying to get some sleep as he traveled homeward."

John smiled and put an ann around Ma's waist.

lO

drawing her close. At one time Peg, still missing the father she had lost, had resented John's open affection for Ma, but no longer. Over and over she saw that he sincerely loved Ma and was a good husband to her, and it was obvious that Ma loved him.

"Tell me more about this Miss Hennessey," John said to Frances. "I heard that the raid took the entire town by surprise. How did she manage to escape the raiders?"

"A merchant with a horse and wagon was fleeing Lawrence. He agreed to let her ride with him."

"That's not very fast transportation. A Reb on horseback could catch up with a wagon in less than a minute."

"They were ahead of the Rebs," Frances explained. "Violet left Lawrence from the north as the raiders entered the town from the south."

"Interesting," he said. "How did she learn they were coming?"

Frances grew flustered. "I don't know, and she was so upset that we didn't bother her with questions. I suppose that people fleeing ahead of the raiders brought the news."

"John!" Ma broke in. "Stop ragging Frances. She brought Miss Hennessey here as an act of kindness because the poor woman was so frightened. You get so curious that you shake a bit of news to pieces the way a dog worries a bone."

John shook his head sadly. "It's Quantrill I'd like to be shaking. The Lawrence raid was a terrible act of revenge on that evil man's part. Word has it that Quantrill led his raiders shouting, 'Kill! Kill!' The man must be mad."

John's news didn't surprise Peg. Marcus Hurd, who was undoubtedly the dirtiest, meanest boy in school.

was nevertheless a good source of information. One day before class, Marcus had to

ld them in gory detail what he'd heard about the collapse of the makeshift prison in Kansas City, in which many of the wives and women friends of Quantrill's men had been killed or badly wounded. Quantrill had vowed to get even.

"Vinny Ottman came by today to get his horse shod," John said. "The poor man was broken. It seems his cousin Frank was caught by a Union patrol, accused of spying for the Confederates and hanged on the nearest tree."

"Oh, dear," Ma said. "I'll go pay a call on Vinny and Jane."

"Why did they hang him on the nearest tree?" Peg asked. "Why didn't they take him to jail?"

"There's no quarter given to spies, my girl," Mr. Murphy said. "On both sides, if a spy is caught, he's immediately hanged."

With a concerned eye on Peg, Ma pulled away from her husband. "Enough of all this talk of war," she said. "The chicken is browned, the potatoes are baked, and it's time to celebrate Peg's birthday with her favorite supper."

The meal was every bit as delicious as Peg knew it would be. Afterward, Ma prepared a tray, taking it to Miss Hennessey herself, and Frances insisted on doing all the cleaning up.

Peg curled contentedly into a chair by the fire Mr. Murphy had laid in the wide, brick fireplace in the parlor. This was not only a special day for Peg, there was a guest in the house, so the parlor would be readied for her use. How different from their usual routine of spending the evening at the kitchen table. Peg thought. Most evenings she'd be busy with schoolwork. Ma would have a lap full of mending, and John would go

over every inch of The St Joseph Gazette, bits and pieces of which he'd read aloud.

As Peg stretched like a cat, sucking on a piece of the taffy Frances had brought her and luxuriating in the warmth from the fire, Ma came downstairs with a report that Miss Hennessey had eaten every bite of her supper and had settled back in bed, ready once again to sleep.

"The color's come back into her face," Ma said with satisfaction as she placed her oil lamp on the table. "With rest and good food she'll be herself in no time at all."

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island