- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Read online

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

With grateful thanks to

Mary Ellen Johnson

who founded the

Orphan Train Heritage Society of America

in order to honor the orphan train riders

and preserve their history.

A Note from the Author

During the years from 1854 to 1929, the Children's Aid Society, founded by Charles Loring Brace, sent more than 100,000 children on orphan trains from the slums of New York City to new homes in the West. This placing-out program was so successful that other groups, such as the New York Foundling Hospital, followed the example.

The Orphan Train Adventures were inspired by the true stories of these children; but the characters in the series, their adventures, and the dates of their arrival are entirely fictional. We chose St. Joseph, Missouri, between the years 1860 and 1880 as our setting in order to place our characters in one of the most exciting periods of American history. As for the historical figures who enter these stories—they very well could have been at the places described at the proper times, to touch the lives of the children who came west on the orphan trains.

>?«--

A 2iiiisib

KSSJK^CW FS«J»M rV.F. MM TJfV I'l F4^R

^MJj^3 M^^ SBS3 THBM.

I

lEECIANTS, FARMERS

AND FRIENDS GENERALLY • r« req*xeet«d to give publicity to the above *»•!> m'cti.oauap.,

IDGEN, Agent

"Grandma, will you read us another story from Frances Mary's journal? Now? Right now?" Jeff Collins begged as he pushed his chair back from the breakfast table.

Jennifer Collins scowled at her twelve-year-old brother. ''After we do the dishes," Jennifer reminded him, glad that it was his turn to clean the kitchen and not hers.

"That's right," Grandma said, and smiled at Jennifer. "After dishes, and after beds have been made."

"Ooops!" Jennifer said, and scrambled out of her chair, heading for the stairs. She should have remembered to make her bed and pick up the clothes she'd scattered around her room. Grandma's house would be their home until the end of summer, when Dad would return from his overseas assignment and they'd learn where the family would be transferred.

Jennifer remembered her early reluctance at spending what she was sure would be a boring summer in Grandma's

small Missouri town while Mom secluded herself in an upstairs bedroom in order to write a novel.

How wrong she had been!

Ever since Grandma had brought out the journal written by Jennifer's great-great-great-grandmother, Frances Mary Kelly, Jennifer couldn't learn enough about the Kelly family, who had come to St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1860, on one of the orphan trains from New York City.

Thinking about the stories that were to come, Jennifer and Jeff sped through their chores. Soon they were seated in the wicker furniture on the screened porch, while Grandma settled into the rocker opposite them with Frances Mary's journal open on her lap.

Grandma began to read.

We knew war was coming. There was no way to escape it. Even before Abraham Lincoln's inauguration as President of the United States on March 4, 1861, the southern states had begun seceding from the Union; so while we rejoiced that Kansas was granted statehood and admitted to the Union on January 29, we could not forget our fear of what might happen to a country so bitterly divided.

In February all our fears became realities. Representatives from the southern states met in Montgomery, Alabama, and adopted a constitution for a Confederate government. The Confederacy even inaugurated its own president, Jefferson Davis. With the formation of a separate rebellious government, we gave up any hope of solving the slavery issue peacefully. It would be North against South, neighbor against neighbor, and we were all fearful.

I confess that I carried an extra worry within my heart. I knew my brother Mike, loyal, brave, and impulsive, wouldn't be content to remain at home with his foster mother, Mrs. Taylor, when the activity of war

beckoned all around him — especially since Captain Taylor, his foster father, would be leading his own company into battle.

After the first shot was fired upon Fort Sumter on April 12, Mike proved that I was right about him. In his subsequent letter Mike wrote with excitement about volunteers being trained and plans being made at Fort Leavenworth. Did Mike wish to participate in these plans? I hurried to write and remind him that war was not an exciting adventure, it was horrible. I pointed out that men must be at least sixteen in order to serve as soldiers, and he was only a boy of twelve.

''Twelve, but close to thirteen, " Mike finally replied. 'And Fve grown an inch or more since you last saw me. Captain Taylor and his company left by train for Virginia to join Brigadier General McDowelVs regiments, but Fort Leavenworth's still busier than the New York docks with five ships in port. There's an old feller here named Jebediah — we call him Jeb — and he's taught me all ten drum calls a drummer boy needs to know. "

In spite of the warm weather, I shivered as I read his parting words: "You may know what is best for you, Frances Mary, but there's no way you can judge what is best for me. Only I can do that. "And then he teased, "Tell me, how can you know anything about war — a gentle (but bossy) girl who's never been near a battlefield?"

"Michael?"

Mike Kelly stretched in his chair and gazed out the window to watch a ragtag group of volunteers straggling in uneven formation across the sunbaked Fort Leavenworth parade ground. Their uniforms were just as haphazard, whatever the supply officer could come up with: forage caps, dark blue jackets that didn't fit, and light blue pants— many of them made of shoddy, a cheap wool mixture that fell apart when it got wet.

The men's shoes were an odd assortment of everything from brogans to boots, with a wisp of hay tied to the left foot, a wisp of straw tied to the right. Sergeant Duncan, frustrated that many of the farm boys didn't know their right foot from their left, had changed the marching cadence from "left . . . right" to "hayfoot . . . strawfoot." In spite of the sergeant's efforts, one of the men, seeming to be still confused, tripped and stumbled over the man in front of

him, and they both fell to the ground. As a purple-faced Sergeant Duncan ordered a halt, Mike chuckled.

"Michael! Try to keep your mind on your lessons."

Mike turned to face his foster mother, Louisa Taylor, who shook her head at him sadly.

"Granted, you're a quick student and good at both reading and mathematics, but you can't learn what I'm trying to teach you and stare out the window at the same time."

This pretty young woman who sat across the table from him tried her best to look stem, but her eyes began to twinkle, and a smile spread across her face.

Mike grinned in response. "That's a sorry group of soldiers out there on the parade ground," he said. "I can't see how they'll march to battle if they can't stay upright."

Louisa's smile vanished, and her eyes darkened with worry. "If only they didn't have to go to battle," she said. "If only our leaders could have solved the slavery problem peacefully, we wouldn't be at war."

"Those Rebs weren't about to listen to reason," Mike answered, but he broke off. That wasn't what Mrs. Taylor wanted to hear. "Don't worry about the captain, ma'am," Mike said, and reached across the table to touch her hand. "He's a good, well-trained officer. He'll come through this war all right."

Louisa looked at him hopefully. "I thank God that the captain's life was spared during the skirmishes in Virginia. Big Bethel was a sad defeat for our Union Army, but the captain wrote that the men acquitted themselves as well as could be expected, since most were inexperienced volunteers."

Mike shook his head angrily. "The Rebs shouldn't have won a single battle. I wish I'd been there. I'd have helped to change the score!" Mike could visualize himself in the thick of the fight, charging ahead through the smoke and gun blasts. Some of the volunteers had turned and run; Mike would have pressed forward no matter what.

Louisa stretched across the table to tousle Mike's curly red hair. "It's a blessing to all of us that you aren't old enough to be called to fight. You should be safe here at the fort, and if our many prayers are answered, the war will be over soon."

Mike squirmed uncomfortably in his chair. Safe at the fort? Did they think he was a small child, needing protection?

Louisa seemed not to notice Mike's fidgeting. "I enclosed your letter to the captain in the letter I sent to him this morning," she said. "The best thing we can do is to write to him often." Sitting a little straighter in her chair, Louisa picked up Mike's copybook. "Now then, let's get back to the lesson."

But from outside the open window came the ever louder stamp of boots and Sergeant Duncan's booming voice as he counted cadence, and Mike couldn't resist twisting in his chair for one quick look.

"Oh, Mike, Mike," Louisa said with an exaggerated sigh. "All right, run outside and watch. We'll work on your lessons later."

Mike nearly upended his chair in his hurry. "It's exciting —all the comings and goings and bugles and drumbeats and such."

"War is not exciting," Louisa told him.

"Ma'am, you sound like my sister, Frances Mary," Mike teased, and he ran outside to the front porch of the officers' quarters, which faced the parade ground. Mike's heartbeat quickened as a flag bearer passed by, and he stood stiffly at attention. Women don't understand about these things, he told himself.

For a moment Mike could see himself holding the Union flag high, leading the way as mounted officers and foot soldiers followed him into battle. Cannonballs whizzed past, and gunshots rang in his ears, but Mike bravely pressed on.

The dream of glory was short-lived. Mike was more than

three years shy of the accepted age for becoming a soldier. Sergeant Duncan had laughed when Mike had told him he wanted to enlist.

"Don't try lyin' about your age with me, boyo," the sergeant had said with a whoop of laughter. "We've got plenty of men willing to fight for the Union, so there's been no talk of forming a little kiddies' army as yet."

He'd laughed again, and Mike had stalked away, angry. If the sergeant only knew it, Mike would make a better soldier than any of those raw recruits on the parade ground who were still trying to pick up their feet and put them in the right places without causing disaster.

Todd Blakely, Captain Blakely's son, appeared across the parade ground and waved to Mike, yelling, "Come on! Jeb wants to see us!"

Dodging two sutlers' wagons loaded with supplies for sale and a row of tents that had sprung up sometime during the night, Mike ran around the end of the parade ground to join Todd.

Todd had a shock of thick blond hair and gangly arms and legs. His arms constantly thrust out of sleeves, and his pants legs were always too short, no matter how often his mother let out the hems. Todd had become Mike's best friend at the fort, and it was Todd who two weeks earUer had introduced Mike to Jebediah, the elderly soldier who knew all the drum calls.

Gap-toothed Jebediah, whose limp testified to the two shots he had taken in the Indian wars, had led the boys to a tack room at one end of the stables, which were pungent with the acrid odors of hay and the sweat of horses. There, Mike and Todd sat on a bale of hay, as Jebediah carefuUy took a large package from a shelf and slowly unwrapped its cloth covering to expose a drum.

"Belonged to a lad of only nineteen who went down with an arrow in his back," Jebediah'd said. "I snatched up his drum and kept the beat goin'. Stuck by my captain and

followed his orders to beat advance for the men. We won that battle, and I got praised for my actions by my captain. Even though our company later got a new drummer with his own drum, I hung on to this one because I knew it would come into good use someday. It's about time for it to go back into service. The drum sounds the orders to the men to advance or retreat. A company's handicapped if it hasn't got a drummer."

He'd motioned to Todd to stand, then hung the drum strap around Todd's neck, adjusting the strap so that the large drum hung just above Todd's knees. Painted on the side of the drum was a faded eagle with wings outstretched and a Union flag that waved in an imaginary breeze.

Jebediah had produced two drumsticks and suddenly, magically, beat out a rat-a-tat-tat that made Mike's heart jump.

"Here," he said, thrusting the sticks into Todd's hands. "You try it. Hold them like this. No, this a-way."

Todd was quicker, but soon Mike got the feel of the drumsticks and picked up the rhythms. Ever since that day, the two boys had practiced the drumbeats whenever Jebediah had given permission.

Now, as Mike and Todd ran into the stables, Jeb met them. "You boys have been practicin' the calls for a good long while," he told them. "Now, suppose you show me what you can do,"

In the tack room Todd performed first. Then it was Mike's turn. He went through all ten calls, from reveille, a sharp rapid beat to wake up the soldiers, to taps, the solemn slow drumming that meant lights out and bedtime. Jeb had said that taps was a call new to this war. Trying not to think too much about the fact that taps was also drummed at funerals, Mike beat out the call, making only one mistake . . . well, maybe two or three.

But instead of praising the boys, Jeb grimaced, showing a mouth with more gaps than teeth. "Good thing you've got

years of practice ahead of you afore you're old enough to join up/' he said to Mike. "Those beats have got to come out smart and sharp enough to inspire the men. Do you think you can lead men into battle with a thud, thud, thud?"

Mike felt himself blush. "I guess I was concentrating too hard on the beat itself. I'll give it another try," he said.

"Maybe by the time you're sixteen, this war will be over," Jeb answered slyly, "and the army won't have much need of drummers."

Mike thought of Sergeant Duncan, who had laughed at his age and his size. "I may be short for being nearly thirteen, but I'll soon start growing fast," he said. "Won't be long before I can pass for at least a year older."

"I'm two years older than Mike and tall for my age," Todd said. "Anybody'd take me for sixteen. Besides, I've got my own bugle and know all the bugle calls. I've been thinking of joining up."

"So you been sayin'." Jeb glanced at Todd from the corners of his eyes. "I been hearin' that some of the companies bein' put together in such a hurry haven't got drummers or buglers and ain't fussy about ages. A boy close to the age to enlist, showin' up at the right place at the right time with a fine drum like this one or a shiny bugle, just might find himself a part of the Union Army."

"Where's this 'right place'?" Todd asked.

"Down south a-ways at Fort Scott, less'n ninety miles or so, they're mobilizin' a lot of foot soldiers, sendin' 'em out nearly as fast as they show up to enlist."

"Ninety miles? That's a long ways to walk," Mike blurted out.

Jeb's lips turned down in a sneer. "No use joinin' the army if you're afraid of a little walkin'. The fightin' never lasts long at a time. It's the walkin' what soldiers do most of." He chuckled. "Don't know if you can make it in just three days' time, but the Second Kansas Infantry, under Col-

onel Mitchell, will be leavin' Kansas City, headed into south-em Missouri."

"Kansas City isn't far!" Mike exclaimed.

Jeb struggled to his feet. "You can stay here and practice," he said. "I gotta tend the horses." But just before he reached the doorway, he turned to face Todd. "I was just a scrap of a youngster when I signed on because my country needed me," he said. "I know how you feel."

Hurt at being ignored by Jeb, Mike waited until Jeb was out of earshot and said, "The Union Army needs both of us."

"Maybe not right now," Todd said.

"You've talked about jo

ining."

"I know, and someday I will. But before my father left for Virginia, he told me the best thing I could do was work hard, study, and take care of my mother and sisters."

Mike said, "Captain Taylor told me nearly the same thing. But we're not children. We can help the Union win the war."

"You're serious, aren't you?"

"Yes. I'm serious."

Todd frowned as he thought. "There's not much I can do to take care of my mother," he said. "If you've noticed, the women seem to take care of each other."

Mike nodded. "And because of the orderlies' help, we don't even have many chores."

"So there's not much we're needed for around here."

"You might even say we're in the way." Mike looked at the drum and then at Todd. "Captain Taylor didn't exactly forbid my joining up—at least, he didn't put it in those words. What about your father?"

Todd scrunched up his forehead as if he were trying hard to remember. "When I said I wished I was old enough to join the army, my father told me he just hoped the war would be over before I had to make that decision."

"So he didn't say, 'You can't become a drummer for the Union Army.' "

"No," Todd said. "He didn't."

As excitement began to shine in Todd's eyes, a slight twinge of guilt that had been pestering Mike dissolved.

"I've heard the Rebs are tough fighters," Todd said. "The army needs all the help it can get."

Mike grinned. "Sergeant Duncan said that under fire some of these Union volunteers get scared and run. I'd never run."

"Me neither."

"The army badly needs drummers and buglers. Jeb said so. We know how to beat the calls. It's a real waste if we don't do anything with what we know."

"It's not only a waste. It's like working against the Union when we're needed and don't go."

Mike's heart thumped rapidly, and his voice dropped to almost a whisper. "Then what do you say we make our way down to the Second Kansas Infantry in Kansas City and see if they can use us?"

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

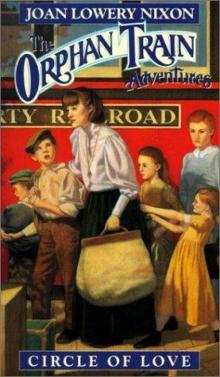

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

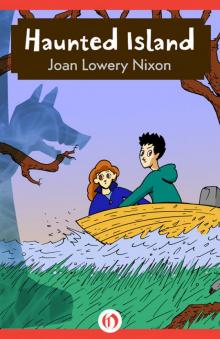

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island