- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

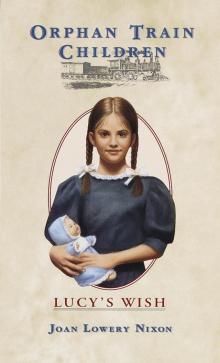

Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Read online

Books by Joan Lowery Nixon

FICTION

A Candidate for Murder

The Dark and Deadly Pool

Don’t Scream

The Ghosts of Now

Ghost Town: Seven Ghostly Stories

The Haunting

In the Face of Danger

The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Kidnapping of Christina Lattimore

Laugh Till You Cry

Murdered, My Sweet

The Name of the Game Was Murder

Nightmare

Nobody’s There

The Other Side of Dark

Playing for Keeps

Search for the Shadowman

Secret, Silent Screams

Shadowmaker

The Specter

Spirit Seeker

The Stalker

The Trap

The Weekend Was Murder!

Whispers from the Dead

Who Are You?

NONFICTION

The Making of a Writer

With thanks to Amy Berkower and Dan Weiss,

who envisioned the orphan train stories

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental

Text copyright © 1998 by Joan Lowery Nixon and Daniel Weiss Associates, Inc.

Cover art © by Lori Earley

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York. Originally published in hardcover by Delacorte Press, New York, in 1998.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 978-0-385-32293-5 (trade) — ISBN 978-0-440-41306-6 (pbk.) — ISBN 978-0-307-82731-9 (ebook)

First Delacorte Press Ebook Edition 2013

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

A Note from the Author

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Epilogue

Glossary

About the Author

A Note from the Author

In the 1850s there were many homeless children in New York City. The Children’s Aid Society, which was founded by Charles Loring Brace, tried to help these children by giving them new homes. They were sent west and placed with families who lived on farms and in small towns throughout the United States. From 1854 to 1929, groups of homeless children traveled on trains that were soon nicknamed orphan trains. The children were called orphan train riders.

The characters in these stories are fictional, but their problems and joys, their worries and fears, and their desire to love and be loved were experienced by the real orphan train riders of many years ago.

More orphan train stories by

Joan Lowery Nixon

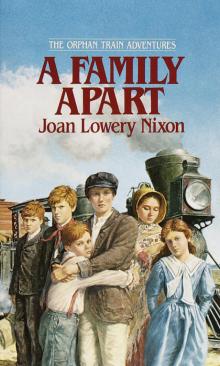

A FAMILY APART

Winner of the Golden Spur Award

CAUGHT IN THE ACT

IN THE FACE OF DANGER

Winner of the Golden Spur Award

A PLACE TO BELONG

A DANGEROUS PROMISE

KEEPING SECRETS

CIRCLE OF LOVE

LUCY’S WISH

WILL’S CHOICE

From the journal of

FRANCES MARY KELLY, JULY 1866

Our orphan train is on its way to Missouri. I hope with all my heart that the children in my care will be placed out with loving foster parents.

The children try to be brave. But I can see the fear in their eyes: Will I be chosen? Will anyone want me?

Some of the children want only to be comforted, but others ask for promises they must know I can’t make. Today ten-year-old Lucy Griggs tugged at my skirt. Her shy smile and pleading gaze touched my heart.

“Will you help me find a family?” she asked.

“Of course,” I told her.

“I want a special family,” Lucy said. “I want a mother and a father and a little sister for me to love. I’ve always wanted to have a little sister.”

My heart ached for Lucy. When she was six, soon after coming to the United States from England, her father was killed in an accident. When her mother died a few weeks ago, Lucy was evicted from the one-room apartment she had shared with her mother. Lucy had no one to care for her until she was rescued by the Children’s Aid Society.

I tried to help her face the truth. “Lucy, dear,” I said, “if people already have one child, they may not have enough money to take care of another child.”

But Lucy’s eyes shone. “Oh, yes, they will! You see, their little girl will want a big sister. She’ll be looking for me.” She held out the doll she calls “Baby” and said, “I’m going to share Baby with my little sister.”

I hugged Lucy, unable to answer. Please let it be so were the only words that came to my mind, for I have no way of knowing what will happen to Lucy.

Lucy Amanda Griggs squirmed between the two large boxes she had found in the alley. Even though she was very tired, she couldn’t sleep. The ground was hard and lumpy, and the bright morning sunlight forced Lucy to open her eyes.

She tugged her ragged shawl up to cover her head. Her hair felt damp and greasy. How long had it been since she’d had a bath? Lucy couldn’t remember.

She smiled at Baby, cradling the doll in her arms. One side of Baby’s face was covered with a spiderweb of cracks. And there was a hole in her cloth body, where Lucy had to keep poking the stuffing back inside. Lucy didn’t care. She had found Baby in a trash bin. She knew that Baby needed her, and she needed Baby. The cracks, the faded dress, and the hole didn’t matter. From the moment Lucy saw Baby she loved her.

Lucy rocked Baby and sang to her. It was a soft, sleepy song that Lucy’s mother had always sung to her. “Rock, rock, my baby-o. Rock, rock, my baby.”

But Lucy’s song melted into tears as memories of her mother swept over her.

She angrily brushed the tears away. Crying didn’t help. Lucy remembered the time when Mum had told her that Father had been killed in an accident. It was four years ago. Lucy and Mum had clung to each other and sobbed, but their tears hadn’t brought Father back.

Lucy shivered and hugged Baby tightly. She thought about the terrible day when Mum had died of cholera. That was four—or was it five?—weeks ago. Inspectors from the Metropolitan Board of Health had hurried into Lucy and Mum’s room. The inspectors were afraid that the disease would spread. Cholera had already killed more than two thousand New Yorkers. Even before the inspectors left, the landlord, Mr. Beam, had ordered Lucy to leave the building.

He had clutched her shoulder as he pushed her toward the doorway. “It’s a matter of business. I’ve got to clean up that room and rent it to someone who can pay,” he’d said. His eyes were not on Lucy, but on the inspectors.

Lucy had been so frightened that her heart had pounded. She’d clenched her hands to keep them from shaking. “But, sir, I’ve got nowhere to go,” she had pleaded

.

Mr. Beam had glanced nervously at the inspectors. He had lowered his voice and answered, “I can’t worry about your problems. I’ve got enough of my own. The Board of Health like to have ruined me last February. They blame the landlords for the cholera that swept through this city.”

He had cleared his throat with an angry harumph! and added, “Meeting their demands to clean up and make repairs cost me a great deal of money. I’ve nothing to spare, so don’t be coming to me for help.”

Weak from fear, but with no choice, Lucy had wandered out to the street. She had plopped down on a curb, heedless of the hooves of the horses and the heavy wagon wheels that rumbled near her toes. She had wept in sorrow, but her tears hadn’t brought Mum back. They hadn’t helped at all.

As Lucy’s sobs became dry shudders, she had looked up and seen the Olneys’ butcher shop across the street.

Sometimes Mum, with Lucy in hand, had stopped by the shop. Sometimes she had managed to come up with enough coins to buy a small piece of meat or a soup bone. And sometimes Mum had played with and talked to the Olneys’ son, Henry.

Mrs. Olney looked unhappy whenever anyone asked her about Henry. “Never been right in the head since he was born,” she said. “Can’t nothin’ be done about it.”

Mum had treated Henry the way she treated everybody else. Henry tried to talk to Mum, and Mum seemed to understand. When she paid attention to Henry, he smiled and laughed.

Once Lucy overheard another neighbor say, “I’m always kind to the lad. I tell myself, ‘There but for the grace of God go I.’ ”

Under her breath, so that only Lucy could hear, Mum had whispered, “I tell myself, ‘There go I.’ ”

Later, when they were alone, Lucy had asked Mum, “Why is Mrs. Olney always so cross? Why doesn’t she ever talk to Henry?”

Mum had shaken her head sadly. “Mrs. Olney wanted a strong, healthy child who could work in the shop and learn his father’s trade. She’s so bitter, she can’t see that Henry has feelings like everyone else.”

Lucy thought about the blue-and-green marble Mum had found and had given to Henry. He had laughed and clapped his hands with joy. “You know what Henry likes, and you can talk with him,” Lucy had said. “I wish Mrs. Olney would try.”

“Maybe someday she will,” Mum had said. “For now, you and I will be Henry’s friends.”

Lucy shook away the memories and slowly got up from the curb. She crossed the street, darting between the carts and wagons, and entered the butcher shop.

Mr. Olney was not in sight. Mrs. Olney stood behind the counter. Gruffly she said, “G’dafternoon, Lucy. Sorry to hear about your ma. She was a good woman.”

Lucy nodded, too frightened to speak.

“Well, what’s done is done. That’s the way of life. So let’s get on with it,” Mrs. Olney said. “Did you come to buy a small chop? A pat of ground beef?”

Trying not to look at the blood-soaked wooden chopping block, Lucy spoke up. “I have no money to buy food, and I have nowhere to live. I’ve come for a job. I’ll sweep. I’ll scrub. I’m ten years old—big enough to do hard work.”

Mrs. Olney’s lips turned down, and she gave a loud sniff. “You’re just a slip of a girl, Lucy Griggs. You’re scarcely big enough to lift and carry a bucket of water. But if it’s hard work you want, I’ve got plenty of that for you. In turn, you’ll get two meals a day and a pallet to put down by the fire.”

“Thank you,” Lucy whispered.

Hot tears rushed to her eyes, but Mrs. Olney snapped at her. “No time to waste on tears. Understand? Get a scrub brush, a large rag, and a bucket from the back room. Those Board of Health inspectors might poke their noses round here, so the floor and walls will need to be scrubbed down.”

Henry followed Lucy. As she bent to pick up a bucket, he reached out and gently touched her tear-damp face. Lucy couldn’t tell what he said, but she heard the question in his voice.

“I’m sad, Henry,” she told him. “I’ve lost my mum and I miss her. I’m sad.”

Henry seemed to understand. His face looked sad, too. But in an instant he brightened. He pulled the shiny blue-and-green marble from his pocket and pressed it into Lucy’s hand.

Lucy tried to give it back. “Mum gave this to you,” she said.

Henry smiled and nodded as he backed off, his hands behind him.

“You really want me to have this,” Lucy said, surprised at the joy in Henry’s eyes. “Thank you, Henry. It’s a beautiful gift. I’ll keep it forever.”

“Where are you, girl?” Mrs. Olney’s voice was sharp.

Lucy quickly tucked the marble into her pocket, picked up the bucket and rags, and ran to fill the bucket.

Lucy worked hard each day from well before light until late at night. But, remembering what Mum had said, she always found time to talk to Henry. She could understand some of Henry’s speech. She could make him smile. Sometimes, together, they played with the marble.

Then one morning Lucy awoke ill and feverish. Everything went wrong that day. She spilled a pitcher of milk, and then dropped and chipped Mrs. Olney’s heavy china platter.

“You’ll have to go,” Mrs. Olney grumbled. “I can’t waste any more time coddling the likes of you. One problem child’s enough to care for.”

Shaken, Lucy begged, “Could I say good-bye to Henry?”

“As if he’d understand!” Mrs. Olney snapped. “Can’t you see how busy I am? The last thing I need right now is the two of you underfoot. Get your things and go!”

Lucy ran, clutching the marble in her pocket. I won’t forget you, Henry, she promised.

In her shelter Lucy shuddered at the unhappy memory. She held Baby even more tightly.

She was startled when a low voice outside broke into her thoughts. “Lucy! Hsst! Lucy!”

Lucy recognized the voice, so she pushed aside one of the boxes. Her friend Joey, a wiry, dark-haired boy, smiled at her. “Good. You’re still here,” he said.

Lucy smiled in return. “Thank you for helping me last night,” she said. “When Mrs. Olney threw me out, I didn’t know where to go.”

“Lots of kids sleep in alleys,” Joey answered. “It’s just lucky I knew about this place and got you here before anybody else found it.” He crawled into her shelter. “Feeling better?” he asked.

Lucy nodded. “The apple and bread you gave me must have helped.”

“So you’re not hungry anymore?”

Lucy’s stomach gave a hollow rumble. Both she and Joey burst out laughing.

He reached inside his ragged jacket, pulled out a banana, and held it out to Lucy.

Lucy knew that Joey had no money to buy such a treat. She suspected that the banana had disappeared from a peddler’s cart. But she was too hungry to ask questions. She grabbed the banana and gulped it down.

Joey’s eyes twinkled with mischief. “If you could make a wish, what would it be? A full stomach? A clean bed in a real house?”

Lucy surprised even herself as she said, “I’d wish for someone to love me.”

Joey blinked and smiled sadly. “I can’t give you that wish, but I can give you the next best thing.” He tugged a scrap of paper from his pocket.

“One of my chums who lives in the tenements got a letter,” he said. “It’s from a lad name of Bertie Jarvis. He used to be one of us, living on the street. Then he went west on an orphan train.”

“What’s an orphan train?” Lucy asked.

“They’re trains that take kids who live on the streets to homes on farms out west. Now, listen. I’m not good at reading, so I was careful to remember the words. The lad wrote that the people who took him in were treating him swell. He said, ‘Tell the others. Come west on the orphan trains. Get a new mother and father. It’s a good life.’ ”

Lucy’s heart leapt. A new mother and father? For an instant she could feel the warmth of her own mother’s arms around her. No other woman could ever replace Mum. But if the new mother was part of a family … a family with a litt

le sister for her … “Are you going west?” Lucy asked.

“What? Go to some strange place I never heard tell of? Not me,” Joey answered.

“But a mother and a father …”

“Who needs a mother and father?” Joey asked. “I like New York City. I’m free here to do whatever I like. I don’t want to go nowhere else—especially to a farm where I’d have to work.” He made a face. “Feed the pigs. That’s what they’d have me do. Feed the pigs, and that’s not for me.”

“I want a mother and father,” Lucy said. “And a little sister. They could make my wish come true.” She rubbed her nose hard so tears wouldn’t come. “How can I find out about the orphan trains?”

Joey grinned and handed her a scrap of paper. “I got my chum to write down the address of the Children’s Aid Society. The people there send orphans to homes in the West.”

Thankful that Mum had taught her to read, Lucy studied the address.

“I know where the offices are, and I’ll take you part of the way,” Joey said. “But after that you’ll have to find your way to the Society’s offices by yourself. I got myself in a bit of trouble with an officer on that beat, so it’s best I not show my face around there for a while.”

Lucy scrambled out of the shelter and stood up. The hot sun beat against her back. “That means I won’t be seeing you again,” she said.

For a moment Joey looked so lonely that Lucy wished she could hug him. But Joey wouldn’t know what to do with a hug.

“I hope,” he said in a rush of words, “I hope you get your wish, Lucy.”

“Thank you,” Lucy said. “But don’t tell it to anyone. Wishes are supposed to be kept secret.”

“Then it’s my secret, too,” Joey said. He gently punched her shoulder and gave her a smile.

“Joey …,” Lucy began. She wondered how she could find the words to thank him for all that he’d done to help. But before she could, Joey turned to leave. “C’mon, Lucy. We ought to get moving.”

Lucy smoothed her hair from her eyes, wrapped Baby snugly into her shawl, and followed Joey in the direction of the Children’s Aid Society.

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island