- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

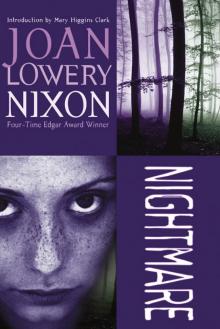

Nightmare

Nightmare Read online

Praise for

Nightmare

An ALA Quick Pick

“Readers will once again fall under Nixon’s spell as they enjoy this page-turner.”

—School Library Journal

“This one continues [Nixon’s] inimitable blend of horror and whodunit.… The climactic confrontation is unforgettable.”

—Booklist

“Nixon’s fans will undoubtedly welcome this book as a rainy day read.”

—Voice of Youth Advocates

“A taut, well-constructed mystery by a writer who will be missed.”

—Kirkus Reviews

Books by Joan Lowery Nixon

FICTION

A Candidate for Murder

The Dark and Deadly Pool

Don’t Scream

The Ghosts of Now

Ghost Town: Seven Ghostly Stories

The Haunting

In the Face of Danger

The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Kidnapping of Christina Lattimore

Laugh Till You Cry

Murdered, My Sweet

The Name of the Game Was Murder

Nightmare

Nobody’s There

The Other Side of Dark

Playing for Keeps

Search for the Shadowman

Secret, Silent Screams

Shadowmaker

The Specter

Spirit Seeker

The Stalker

The Trap

The Weekend Was Murder!

Whispers from the Dead

Who Are You?

NONFICTION

The Making of a Writer

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2003 by Joan Lowery Nixon

Cover photographs © Andy Katz/Indexstock (top); © Roxann Arwen Mills/Photonica (bottom)

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in hardcover by Delacorte Press, New York, in 2003.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web! randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 978-0-385-73026-6 (trade) — eISBN: 978-0-307-43358-9 (ebook)

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

To Shirley Lyons,

a superior teacher,

who enriches her students with the love of reading

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

About the Author

CHAPTER 1

Shades and shadows slithered over and around her, trailing wisps of damp air, sticky-sweet honeysuckle, and the acrid smell of rotting leaves. Her heart pounded, and she grunted with exertion, struggling to get through the tangle of vines, knowing—even in her sleep—what she would find when she broke free. The crumpled body lay half in, half out of the water, eyes stretched wide with horror, mouth open in a scream no one could hear.

In her nightmare the body was always there.

Emily Wood’s mother twisted, reaching from the front seat of the car to clutch Emily’s knee. “Wake up, love,” she said, her voice filled with concern. “You’re having a bad dream again.”

Emily gasped for breath as she opened her eyes to the overbright early-afternoon sun that flooded the car. In spite of the air-conditioning, she was clammy with sweat, and her mouth felt dry and fuzzy. She struggled to sit upright, pushing back damp strands of the curly, pale hair that had fallen over her face, and willed the familiar nightmare to vanish from her mind.

Mrs. Wood’s face sagged with worry. “Emily, if you would only tell us about the dream and talk about why it frightens you … perhaps if we found a good therapist—”

“It’s only a stupid dream, Mom. It doesn’t mean anything. I don’t want to talk about it. I just want to forget it.”

“But this nightmare has recurred ever since you were a little girl, and now you’re sixteen—almost seventeen. Isn’t it time that—”

“Mom! Please!”

Emily’s father, Dr. Robert Wood, quickly glanced from the road, then back again. “Let it go, Vicki,” he said softly. “We’re almost there.”

Mrs. Wood swung forward, ducking her head and burrowing her shoulders into the contoured padded leather of the passenger seat. “I was only trying to help her,” she complained, as if Emily couldn’t hear. “She has never let me help her. It’s like her hair. If she just let me take her to a good stylist …”

Emily didn’t respond. She was tired of trying to explain to her mother that talking about it would make the nightmare more real. The bad dream had first popped into her mind, terrifying her, when she was much younger. Had she been eight? Ten? And every now and then it would unexpectedly reappear. The dead body … the blood on its face … the sickening smell of too-sweet honeysuckle blossoms. Emily was completely puzzled about the nightmare and what it might mean. She had never told anyone what she saw in the dream. She was sure she never would.

The car slowed and turned into a wide drive under an arched sign that read CAMP EXCEL.

Emily made a face. Camp Excel? Who did they think they were kidding?

Her mother sat upright and, in what Emily thought of as her let’s-all-be-in-a-happy-mood voice, began commenting about the beautiful rolling hills and the bursts of gold black-eyed Susans and pale Queen Anne’s lace that dotted the roadside. Her father added a few enthusiastic comments about the beauty of the Texas Hill Country in contrast to the flatness of Houston, but Emily slumped against the backseat, unable to believe what was happening to her.

It had been no surprise when teachers had labeled her an underachiever. The surprise was that anyone expected her to do any better. Her oldest sister, Angela, had aced every test she’d ever taken. She’d been valedictorian of her high school graduating class and was now among the top ten at Harvard Law School, planning some day to join their mother’s law firm. Monica, next in line, was also valedictorian. She had chosen to follow in their father’s medical footsteps and attended the University of Southern California, majoring in premed.

Angela and Monica gave speeches, led programs, and walked across stages to win honors and medals. The idea of trying to match what her sisters did, in rooms filled with eyes staring at her, terrified Emily. Content to disappear in any crowd and in any classroom, Emily was comfortable being little known and hardly ever noticed. She didn’t even mind being classified as an underachiever, if that was what it took to be invisible.

Emily suppressed a sigh, wishing everyone would just

leave her alone. It was plain bad luck that her tenth-grade guidance counselor had called her parents, excited about Camp Excel, a new, intensive six-week experimental summer program for students who were not performing to their abilities.

“It certainly wouldn’t hurt to send you, darling,” Mrs. Wood had announced at the dinner table. “Nothing else—rewards … tutors … praise … Nothing we’ve tried has helped.” She had tucked a loose strand of her light, gray-streaked hair behind her ears and had smiled encouragingly at Emily. “According to Mrs. Carmody, Dr. Kendrick Isaacson has developed an absolutely marvelous summer program to help underachievers learn to do their best. He’s gaining fame among both psychiatrists and educators.”

“I never heard of him,” Emily had said. “I bet you didn’t, either, until Mrs. Carmody told you about him.”

“Of course I have. His field is psychology. Patty Foswick, my friend in Dallas, has raved about him and urged me to take you there for an evaluation. But I realized that Dallas would be too far away for you to do any extended work with him, but in the Hill Country resort they’re using for the summer school—”

Emily’s father had interrupted. “Is he in private practice?”

“No,” Mrs. Wood had answered. “He’s one of the founders of the Foxworth-Isaacson Educational Center in Dallas.”

Emily had dropped her fork with a clatter, her fingers suddenly unable to hold it. For an instant she was numb, unable to see or breathe or think.

“Emily?” she’d heard her father ask from a long distance away. “Emily? Is something the matter?”

Gripping the edge of the table, Emily had forced herself to take a deep breath. As she’d felt her mother’s hand clamp onto her forehead, she’d opened her eyes. “I—I’m okay,” she’d said. “For a moment I just …”

She couldn’t finish the thought. She had no idea why she’d suddenly felt a horrible fear rush through her body. It didn’t make sense, so there was no way she was going to say anything to her parents about it. She’d repeated the words over again in her mind, The Foxworth-Isaacson Educational Center. Had she heard the name before? She had no recollection of it. So why had it made her so afraid? Emily could find no explanation.

“She isn’t running a fever,” Mrs. Wood had said, and had taken her hand away. “But did you see, Robert? The color absolutely drained from her face. I thought she was going to faint. Is there some new virus going around Houston?”

“Nothing out of the ordinary,” he’d answered.

Emily had been aware that her father was studying her, so she’d refused to look in his direction. She’d deliberately picked up her salad fork and poked at the bits and pieces of pot roast and noodles on her plate, still puzzled by what had just happened.

Dr. Wood finally had asked, “Vicki, have you ever visited this educational center?”

“No,” Emily’s mother had answered. “But, as I told you, I’ve heard glowing things about it, even before now. Patty—you remember Patty. I went to school with her—used to live in the same neighborhood as the center. It’s situated on a gorgeous old estate in Dallas. Patty raved about the progress Dr. Isaacson and Dr. Foxworth were making in getting kids back on track. I remember when Emily and I visited Patty and her daughter Jamie for a weekend years ago. Jamie had been nine or ten, about two years older than Emily, and—”

Panic grew like a tight knot, threatening to close Emily’s throat. She’d wanted nothing to do with this educational center. She didn’t know why. She’d only realized that she had to fight whatever her parents were planning. She’d interrupted her mother: “Nobody asked me if I wanted to go to this camp. Don’t I have a choice?”

Emily’s father had spoken firmly, probably the way he spoke to reluctant patients who balked at getting their shots, Emily guessed. “No,” he said. “You don’t.”

“But, Dad, I don’t need—”

“Emily,” he had countered, “you do need.”

“I can’t.”

“You will. If your mother and your guidance counselor think it’s for the best, then it’s for the best. There will be no more discussion about it.”

Emily knew it would be futile to try to change her parents’ minds, so she hadn’t.

The car swung around a curve, and Emily’s memories were broken by her mother’s sudden exclamation of surprise. “This doesn’t look like any summer camp I’ve ever seen,” Mrs. Wood said. “It’s beautiful. The pictures in the brochure don’t do it justice.”

“You told me the property once operated as a resort.” Dr. Wood said. Then he mumbled under his breath, “It costs more than any resort,” but Emily heard.

She glanced out at the low, gleaming two-story stucco buildings that formed a parenthesis around a wide expanse of neatly trimmed lawn. White gravel pathways, bordered with orange and yellow splashes of summer marigolds, connected the buildings. Through the open gap beyond the cozy circle lay the deep blue waters of a lake. The view was attractive. But Emily shuddered, and again she was puzzled by her fear.

Dr. Wood parked in an empty slot near the main entrance of the building on the left. “You made sure your suitcases had yellow tags on them, didn’t you, Emily?”

“Yes, Dad,” she answered. Why did he have to ask?

“Okay,” he said. “Instructions were to stack all luggage behind the car where it could be picked up and delivered to the rooms.” He climbed out of the car, carefully shutting the door behind him.

Before she left the car, Mrs. Wood reached back and gripped Emily’s arm. “Darling,” she said, “don’t look so desperate. Everything here is going to be wonderful.”

As Emily tried to relax and make her expression blank so that her mother couldn’t read it, Mrs. Wood continued. “We’ll be right here this afternoon for parent orientation. Right here with you, Emily.” Her voice went up a cheerful notch. “And by the time we leave you won’t even miss us because you’ll have made some lovely new friends.”

“And we can all go out and play,” Emily muttered, even though she knew she wasn’t being fair to her mother, who was only trying to help.

Sighing, Mrs. Wood left the car and Emily—knees wobbling—managed to climb out. What is the matter with me? she wondered as she leaned against the open door. Why should I be so afraid?

Trying to steady herself, Emily stood quietly, eyes closed, breathing in the sharp, acrid scents of sunbaked pine, marigolds, and newly cut grass.

“Come, Emily,” she heard her father say. “The office is this way.”

They entered a large, bright room that must have once been the lobby of the former hotel. It still looked like a hotel lobby, with groupings of sofas, tables, and high-backed chairs, and Emily wondered if the hotel furniture had been part of the sale.

The lobby was filled with teenagers and adults. The parents looked hopeful and somewhat intimidated, and they hovered near their offspring like hens with their chicks. The staff members were dressed in matching red polo shirts and khaki slacks or skirts, all so obviously brand new they looked like costumes in a play instead of leisure clothes. Smiles beaming and right hands extended, they greeted Emily and Dr. and Mrs. Wood, pulling them into the crowd.

After she had murmured countless hellos to faces she’d never seen before, and heard names immediately forgotten, Emily moved back against a wall. Leaving her parents to chat with some of the staff, she quietly studied the people in the room who were her own age.

They mostly looked like the kids in her high school in Houston, except for one tall guy whose shoulders curled down in a slouch and who wore a way-out-of-season wool knit cap pulled over his ears, and a girl whose long hair, gelled and sprayed into spikes, was dyed billboard yellow with a touch of pink. Her eyes were ringed with heavy mascara, and her lips were a slash of deep magenta.

Emily guessed that in the room there were at least a hundred high school kids and nearly double that in parents.

Before long, however, the parents were shepherded off somewhere for an orientatio

n lecture. As soon as they’d left, a muscular guy wearing a snug T-shirt leaped up onto one of the tables and grinned at the kids.

“Hi,” he said. “By this time I think I’ve said hello to each and every one of you personally, but in case you’ve forgotten my name, I’m Coach Ricky Jinks. You can call me Coach Jinks or Coach or Ricky Jinks or Ricky or anything you like. Just don’t call me late for dinner.”

No one laughed, but Coach Jinks’s pep continued to bubble up and out as though he’d received a standing ovation. “During the next two days I’m going to sign you up for swim team and canoeing and volleyball and you-name-it, but right now they’ve given me the job of assigning you to your rooms and seeing that you get there in one piece.” He eagerly looked around. “Any questions?”

No one responded.

“Okay, then,” Coach Jinks said, his cheerfulness not lapsing for even a second. “I’ll call out names, and you’ll come up here and get your room keys. You’ll be in the building across the courtyard. Your luggage should be in your rooms, so unpack and take a little time to get acquainted with each other, but be back here by five-thirty for dinner. Cook’s barbecuing something—probably whatever roadkill he ran across while driving here. I hope nobody in this crowd is choosy.”

As he jumped down from the table and began calling out names, Emily couldn’t help making a face of disgust. Next to her a short girl snickered. “Six weeks of this?” she said, rolling her eyes. “Those are the kind of jokes my stepfather likes.”

Emily took a good look at the girl. Her sleek, dark hair was long and cut straight across, and her eyes were a deep, intense blue. At odds with her neatly ironed, conservative white blouse and shorts, she wore dangly crystal earrings, a row of narrow silver bracelets on each arm, and an odd rocklike pendant on a silver chain around her neck.

The yellow-pink blonde Emily had noticed earlier moved a little closer. “He told me I belonged on his basketball team,” she said quietly. “I hate basketball even more than I hate his jokes.”

“Taylor Farris,” the coach called, and the girl left, weaving her way to the front of the room.

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island