- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

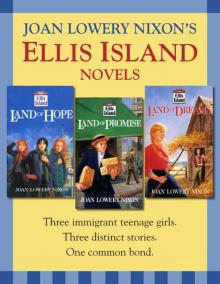

Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels Read online

Books by Joan Lowery Nixon

FICTION

A Candidate for Murder

The Dark and Deadly Pool

Don’t Scream

The Ghosts of Now

Ghost Town: Seven Ghostly Stories

The Haunting

In the Face of Danger

The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Kidnapping of Christina Lattimore

Laugh Till You Cry

Murdered, My Sweet

The Name of the Game Was Murder

Nightmare

Nobody’s There

The Other Side of Dark

Playing for Keeps

Search for the Shadowman

Secret, Silent Screams

Shadowmaker

The Specter

Spirit Seeker

The Stalker

The Trap

The Weekend Was Murder!

Whispers from the Dead

Who Are You?

NONFICTION

The Making of a Writer

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

LAND OF HOPE copyright © 1992 by Joan Lowery Nixon and Daniel Weiss Associates, Inc.

LAND OF PROMISE copyright © 1993 by Joan Lowery Nixon and Daniel Weiss Associates, Inc.

LAND OF DREAMS copyright © 1994 by Joan Lowery Nixon and Daniel Weiss Associates, Inc.

Cover illustration copyright © by Colin Backhouse.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York. The works in this omni edition were originally published separately in hardcover in the United States by Delacorte Press in 1992, 1993, and 1994.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

ISBN 978-0-385-38785-9 (ebook)

A Delacorte Press eBook Edition

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Land of Hope

Land of Promise

Land of Dreams

About the Author

Orphan Train Adventure Series

Thrillers by Joan Lowery Nixon

More Thrillers by Joan Lowery Nixon

Someone near the rail shouted, “There she is! The statue! The Statue of Liberty!” and the passengers turned to see the imposing figure they were approaching. Standing tall on her pedestal, gleaming in the early light, the points of her crown like those on a star, the lady raised high her torch of liberty.

Rebekah spotted Rose and Kristin at the rail. Unable to bear the rush of excitement alone, she squeezed through the crowd until she reached them and wrapped her arms around them as the ship sailed past the Statue of Liberty.

Beyond the Statue of Liberty on the nearest shore were many buildings, but ahead of the ship an astounding series of tall, crowded buildings seemed to rise from the water. “That’s New York City,” a woman said, and Rebekah gasped.

That was New York City? Impossible! How could anyone live in gigantic buildings like that? She thought of her small village, and the land she left behind—the farms with small vegetable gardens near their back doors. Where were the meadows and trees? What had Uncle Avir brought them to? How would they survive?

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 1992 by Joan Lowery Nixon and Daniel Weiss Associates, Inc.

Cover illustration copyright © by Colin Backhouse

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York. Originally published in hardcover by Delacorte Press, New York, in 1992.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 978-0-553-53113-8 (trade) — ISBN 978-0-553-08110-7 (glb) —ISBN 978-0-440-21597-4 (pbk.) — ISBN 978-0-307-82747-0 (ebook)

First Delacorte Press Ebook Edition 2013

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

In loving memory

of my maternal grandparents—

Mathias Louis Meyer,

who came to the United States from

Luxembourg,

and Harriet Louise Prien Meyer

Contents

Master - Table of Contents

Cover

Dedication

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

About Ellis Island

CHAPTER ONE

UNDER the dark shelter of the trees Rebekah Levinsky and her family waited, scarcely breathing, willing themselves to ignore the bitter frost-damp chill of the night air. A pale scrap of moon shed just enough light to illuminate the broad, exposed strip of timber-cut field that cut across the heavily forested land. Centering the strip, a square of yellow light marked the roadside shack of the border guards who patrolled to keep travelers without passports—especially Russian Jews, who were denied passports—from illegally crossing over from Hungary into Austria.

Eight-year-old Sofia’s small hand trembled within Rebekah’s grasp, and Rebekah bent to comfort her, even though she was every bit as frightened as her sister.

“We’ve been waiting such a long time,” Sofia complained.

“Hush!” Their mother’s voice exploded in a sharp hiss of fear. Although Leah stood tall and solid, her face unlined, her dark hair smooth under her kerchief, her voice betrayed her true feelings.

“It’s all right, Leah,” mumbled Elias, Rebekah’s father. “Here he comes now.”

Rebekah looked from her father, small-boned and gentle, to the stocky, heavy-jowled Ukranian guide who strode toward them.

There was a rustle of movement as Rebekah’s older brothers, Jacob and Nessin, moved forward. Rebekah’s grandfather, Mordecai Levinsky, not much taller than she, squeezed close and clasped her right hand. Others in their group clustered more tightly together—all of them neighbors who had made the hard decision to abandon their homes in the shtetl.

Rebekah knew the year 1902 had begun badly for all of them. In early February more than thirty thousand young Jewish socialists had been arrested after th

ey rebelled against the czar’s increasing control over student organizations. During this past month, April, starving peasants had looted landowners’ farms in Poltava and Kharkov, and the head of the Russian secret police had been assassinated. Czar Nicholas, furious with the uprisings and determined to discourage any further revolts among the peasantry, had sent his army to retaliate. It had done so, not only in the cities, but also in the small Jewish towns whose citizens had long been victims of the dreaded pogroms—rampages in which soldiers destroyed entire towns and villages and slaughtered their residents.

Two years before, Rebekah’s Uncle Avir had left for the United States against his family’s advice. Her grandfather repeated what he’d read in an Orthodox journal, which warned Jews to remain in their native land rather than travel to the United States, the new country of “lies and vain dreams.”

In spite of Mordecai’s concerns, Avir and his wife, Anna, had emigrated. In his letters home Avir had raved to his father and brother about the freedom and opportunities in America, and on occasion he had even sent money. “Come to the United States for a life without fear,” he’d urged. “Anna and I constantly worry about your safety.”

Finally, when the soldiers struck in a shtetl not more than a day’s journey from their own, where cousins of Leah’s barely escaped with their lives, Mordecai consulted with Elias, then announced, “It is time to leave. We have no other choice.”

Elias sold what he could of the family’s belongings, pooled his meager savings with his father’s, and purchased seven steamship tickets. The least expensive, in steerage class, cost twenty-seven American dollars apiece! It was hard for Rebekah to imagine that much money.

Now, Rebekah watched as their guide approached. He bent his neck, peering from under his eyebrows, and kept his voice low as he told them in Yiddish, the language they all spoke, “The guards want more money.”

Leah answered quickly, not meeting his eyes. “We have nothing to spare. We must keep enough to pay for our train fares to Hamburg.”

“And food!” Herman Mostel added. Herman had run a shop in the shtetl, but had decided to leave it all behind. “It’s a long journey to Hamburg. We must eat along the way.”

“I can do only so much for you. If you want to cross into Austria …” Moshe, as the guide called himself, shrugged and let his sentence drift into the silence.

Rebekah tucked a strand of long, dark hair under her kerchief and hugged her loose, padded jacket more tightly around her shoulders. The lumps in the lining, where her mother had sewn the family’s travel money, pressed against her hips.

Mordecai, who had been gathering tidbits of information like a squirrel hoarding for winter, had learned about the guides and the way they operated. Guides were a necessity for anyone who wanted to escape Russia, but the guides consistently tried to cheat those fleeing even though they’d already overcharged. It was likely, Rebekah thought, that the Austrian border guards to whom Moshe referred had either been sufficiently bribed or were filled with the vodka Moshe had brought with him and were sound asleep. Whatever Moshe gained from this ruse would go into his own pockets.

Leah fumbled through a deep pocket in her full skirt and pulled out a handful of coins, thrusting them at the guide. Then, as they had planned, others in the group did the same. “This is all we have to give you,” Leah snapped.

Squinting in the darkness to examine the pile of money, Moshe seemed satisfied. He straightened and the coins disappeared into folds in his long, thick coat as he beckoned the group to follow.

Shouldering their bundles, the refugees crossed the open land, stumbling over tree stumps and dying roots, rough stubble and deeply pocked earth, running faster and faster until they reached the shelter of the forest. Mordecai, whose right leg had been stiffened by a childhood accident, tried to keep up but limped after them, arriving out of breath. Huddied together, the travelers turned to Moshe for reassurance.

“Stay within the forest until you’re out of sight of the border guards’ hut,” Moshe cautioned. “Then make your way toward the road. Just a few miles from here you’ll come to the town of Brody.” He paused and smiled before he turned to leave. “You’re in Austria now, far from the Russian cossacks.”

Nessin let out a whoop and beat Jacob on the shoulders, and Leah and the other women began to cry with happiness, hugging their children and one another.

They were no longer in Russia. Now they had come to this moment, Rebekah’s own thoughts were so muddled she could no longer cry. She ached for all the treasures of her fifteen years of life, which she was now leaving forever. What would she do without her best friend, Chava, and her other friends in Ostrog, the place in which she had always lived?

She had often walked with her mother down the twisted cobblestone streets from their house to the marketplace, swinging a basket that soon became heavy with Leah’s purchases. Rebekah loved the noise of the market as peasant farmers and peddlers arrived with vegetables, livestock, hats, shoes, clothing, lamps, and trinkets to see and buy.

“Rebekah, Rebekah, don’t stop so often to gawk,” Leah would tease. “There’s nothing here you haven’t seen before.”

Sometimes on Saturdays in the afternoon peace of Shabbas while their parents were napping, Rebekah and Chava would wander through town, past the small shop where Elias worked as a tailor and past the butcher shop presided over by Chava’s father. They’d sneak quick looks at young men and women, who were dressed in their finest for the afternoon stroll, and giggle over matches that might be made.

Only last summer Chava had said, “Soon it will be our turn.”

“Not that soon!” Rebekah had answered. “We are only fourteen.”

Chava’s eyes had sparkled as she grinned. “It’s a short time between fourteen and seventeen—less than three years. Already my brother Shaul has his eye on you.”

Rebekah’s face had burned with embarrassment. She had already begun to wonder which young man her parents might choose when it came time to arrange her marriage—what girl wouldn’t?—but she had never given a thought to Shaul, a shy, quiet man who worked with his father in the butcher shop. Why, Shaul had rarely spoken to her. Rebekah pushed the idea from her mind. Who knew what might happen in three years?

Rebekah loved to stroll down to the river, which wound through town like a curled ribbon, shimmering at the doorsteps of the rough houses that huddled near the water and rippling gently through fields and rolling hills before it disappeared into the woods. It was there, by the river, where just a few weeks ago, Rebekah had tearfully told Chava that her family was moving to America.

“Why are you leaving?” Chava had demanded. “Your father is doing well in Ostrog as a tailor. How does he know what will happen to him—to all of you—in a strange country?”

It was hard for Rebekah to understand as well. Life in her own shtetl was always so peaceful, no matter what was happening in far-off places whose names had meant nothing to Rebekah until now. She could only repeat to Chava what she had heard her father and grandfather say again and again.

“My father and grandfather are afraid of what the czar might do next. They are sure there will be more pogroms, and the cossacks could be sent to destroy Ostrog. If we don’t leave we may lose everything—even our lives.”

Desperately, Rebekah clutched Chava’s hands and begged, “Come with us, Chava! You and your family! I’ll ask my father to talk to yours and convince him to take his family to America, too!”

Chava hunched her shoulders, hugging her arms in misery. “He wouldn’t listen. His cousin Abram, who left Moscow six months ago, is already in America. He has urged Papa to leave, but he won’t. He insists that this is the home we have always known, and no one will take it from him.” Her lower lip trembled as she added, “Ostrog is your home, too, Rebekah.”

It was painful for Rebekah to speak. “I have no choice, Chava. My father has decided to leave. We must go.”

“All our lives we have been best friends,” Chava had cr

ied. “I thought we would be friends forever.”

“We’ll still be!” Rebekah had protested, but Chava had shaken her head.

Chava’s next words had come slowly and with great effort. “Only in our thoughts. Oh! Rebekah, we’ll never see each other again!”

Rebekah and Chava hugged each other and sobbed.

Rebekah’s throat tightened as she remembered, and her eyes burned. She tried to think of other things: her loving dog, Cossi, who had been too old to make the trip and had found a home with Chava; the warm feather bed she had snuggled in with her sister Sofia on cold winter nights; the huge fireplace at the center of the house that drew the family together both for warmth and for lessons.

Her grandfather had become a well-read man, educated beyond many university students, because he could not do physical labor. His knowledge of the Talmud and literature was well known. He was eager to share it all.

Rebekah loved Mordecai’s lessons. She delighted in the ease with which she had learned to speak and read in Yiddish, which was spoken in the Levinsky home, as well as Russian and English. She treasured her grandfather’s praise.

“You should have been a boy,” Mordecai often told her, his broad smile adding crinkles to his weathered cheeks and chin, and his dark eyes sparkling. “What a fine scholar you would have made.”

Rebekah had fought back the jealousy that rose like sour milk in her throat. Grandfather was right! She should have been a boy! Although her brother Jacob, at seventeen, was quiet and intent in his religious studies, spending hours over the Torah, he was not interested in many other worldly subjects and did poorly in mathematics. Sixteen-year-old Nessin was even less a scholar. Full of mischief and practical jokes, he couldn’t consider a serious subject for more than a minute or two. Rebekah knew she was brighter and quicker than her brothers, but she was a girl, so an education beyond that which her grandfather could give her was out of the question. She knew that in Moscow there were girls who went to school, but they weren’t Jewish and they were of the nobility.

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

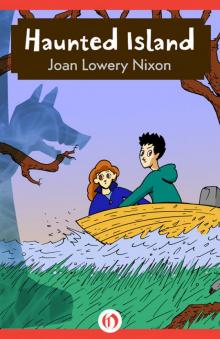

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island