- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

Search for the Shadowman Page 6

Search for the Shadowman Read online

Page 6

Coley Joe went on to describe the rigors of his trip to the noisy, dusty town of El Paso across the miles of scrub-covered prairie.

In his second letter, along with the yucky love stuff, he wrote of widespread gambling in El Paso and numerous saloons—“too many to count.”

His third letter told of making a friend, “a learned gentleman,” who worked as chief clerk for a district judge. Coley Joe wrote:

My friend has offered his help and promises to ride with me to San Elizario, near El Paso, to meet with a gentleman who wishes to sell a herd of Longhorn cattle. A chief clerk’s job is highly respectable but, alas, pays only a small salary, so he is hoping to collect a commission.

Coley Joe went on into a boring comparison of the hardiness and disease resistance of the Longhorn, versus the more flavorful and tender meat of the Angus.

The third letter ended:

I pray that time will pass quickly, my love, so that we may once again be together.

Andy put down the letters and thought hard about what he’d read. He dismissed all the details and focused on the fact that Coley Joe had arrived safely in El Paso and had fully intended to purchase livestock for his family’s future ranch in Hermosa.

He wasn’t running away with the money, Andy told himself. He’d promised Felicity Strickland he’d come back to marry her. Probably a bad move, but Coley Joe had seemed set on it. Andy was sure that Coley Joe wasn’t the kind to make promises, then break them.

Andy gathered up the pages to return them to the drawer in his nightstand. He had his hand on the drawer pull when he froze, gasping at the sight of the faded blue poetry book. It lay not inside the drawer where he was positive he had left it but on the nightstand next to his pillow.

Exasperated because he couldn’t remember handling the book, Andy stuffed it inside the drawer, laid the copies of Coley Joe’s letters on top of it, and shut the drawer tightly. He had to think about what he’d just found out. And he had to sleep. There was no room in his life for more bad dreams!

CHAPTER EIGHT

“So how are y’all coming with your family reports?” Mr. Hammergren asked the next morning in history class.

“Are we supposed to start them already?” Harvey asked.

“When did you say they’re due? I forget,” Nelson asked.

Tiffany Lamb waved a hand. “I’m making a family tree to go with my report. I’ve gone back four generations.”

Harvey groaned. “Is that something we gotta do?”

“No, it’s not something you have to do,” Mr. Hammergren said, “but Tiffany’s idea is a good one. If you’re collecting stories about a lot of grandparents and great-grandparents, it’s a way of keeping their names straight.”

“Does a family tree actually look like a tree? What does it look like?” Lee Ann asked.

“Tiffany? Why don’t you show us?” Mr. Hammergren asked.

Tiffany hurried to the board and wrote her name on the left side in the middle of the board. Then she drew lines leading to her parents’ names, and lines from them to her grandparents’ names and their parents’. There were extra lines leading to names she identified as uncles and aunts. “And these are the names of who they married and their children, and then their husbands and wives and their children.” Pretty soon her handwriting covered the board.

“It doesn’t look like a tree. It looks like a spaceship,” Luke said.

Andy took notes. Maybe if he went all the way back to Malcolm John and Grace Elizabeth and wrote down all the begats—as Miss Winnie called them—there’d be a pattern that might fit together. It was worth a try.

“Anyone else want to share what they’re doing?” Mr. Hammergren asked. “I’d like to hear what directions you’re taking.”

“I sent out a query over the Internet,” Andy said, “and got an answer. A woman faxed me three letters one of my ancestors wrote to his girlfriend.” He grinned. “Dad had told me not to use my real name, so I used the name Hunter.”

Luke and Harvey hooted, but Mr. Hammergren said, “That was a neat idea, Andy. Are the letters going to help you with your project?”

“I think so,” Andy said. “At least I know this guy made it to El Paso.”

When the bell rang, Mr. Hammergren asked Andy to wait a few minutes.

“Why don’t you stick around with me, J.J.?” Andy asked.

“We’re going to be late for lunch,” J.J. complained.

“Hey, what are friends for?”

“Friends don’t make friends miss lunch,” J.J. said as his stomach growled, but he walked with Andy to Mr. Hammergren’s desk.

“Are these letters from the guy who disappeared?” Mr. Hammergren asked Andy.

“Yeah. Coley Joe.”

“So you did trace him to El Paso. Good for you.”

“Thanks,” Andy said. His stomach growled, and he turned toward the door.

“One second,” Mr. Hammergren said. “How far are you going with this search for Coley Joe?”

“As far as I can,” Andy said. “I hope I can find out how and why he disappeared.”

“You’ve already found out he got to this part of Texas,” J.J. said. “Isn’t that enough?”

Andy stared at J.J. “You want me to give up?”

J.J. shrugged. “You know what happened next. Nothing is going to change the facts.”

“Unless I find other facts that prove the first facts are wrong.”

Mr. Hammergren broke in. “Let’s see how your search progresses. If you can bring it to a conclusion, then I’m going to suggest you write an essay about it. There’s a statewide history essay contest I’d like you to enter. First prize is a nice-sized college scholarship.”

“A scholarship?” J.J. repeated.

Andy was puzzled as a strange expression came into J.J.’s eyes. He looked as if he were sorting out every thought that strayed into his head.

Finally, J.J. said, “And an automatic A on our history project?”

Mr. Hammergren chuckled. “You sound like Andy’s agent.”

“I have to be. We’re best friends.”

“Okay. An A on the project.”

J.J. shrugged. “Deal.”

Mr. Hammergren smiled at Andy. “A little fame might go with it, too. The winners are always written up in their local newspapers and are often on the local television newscasts. Think you can handle that?”

Andy laughed. “My mom would like it, but I wouldn’t. She’d make me get a haircut and wear a shirt and tie.”

“We’ll negotiate,” J.J. said. He tugged Andy to the classroom door. “C’mon. We’ve already missed ten minutes of lunch.”

Andy had just enough time to turn and give Mr. Hammergren a thumbs-up. A statewide contest? A scholarship? Wow! He had more reason than ever to find Coley Joe.

As usual, Andy and J.J. walked home together. The row of white columns on J.J.’s front porch gleamed in the afternoon sunlight, and a single browned oak leaf spiraled lazily down to an immaculate green lawn. The air had the spicy smell of freshly cut grass and newly planted marigolds.

“Did Miz Minna put together a family tree?” Andy asked J.J.

“I dunno. Probably.” J.J. looked curious. “Why?”

“Because I wrote down some of what Tiffany said about her family tree, but I can’t remember where some of the people go who aren’t in a direct line. I thought Miz Minna could show me.”

“We can ask,” J.J. said. “C’mon in.”

Miz Minna shut down her computer as Andy and J.J. appeared at her open doorway. She rose with difficulty from her desk chair and hobbled with tiny steps to her large armchair by the window. Sinking into its soft curves and fat pillows, she said, “Y’all sit down, and watch what you’re doing. Careful, Andy. There’s a pitcher of water by your elbow. Don’t tump it over.” She held out a hand toward J.J., who dutifully bent to kiss her forehead.

Andy glanced at the computer. “We didn’t mean to interrupt you, Miz Minna,” he said.

&n

bsp; Miz Minna smiled. “You didn’t interrupt. I was just browsing. There are so many interesting Web sites to browse. And the number keeps growing. There’s a senior citizens’ board, you know. Why, last week … Would you like to hear about the topic that came up last week?”

J.J. got right to the point. “Sure, Miz Minna, but not right now. Andy’s got something to ask you.”

“About family trees,” Andy said.

“What about them?”

Andy was puzzled about the edge that had come into her voice. “I want to write down a family tree for my family, and I think I know how to put together most of it, but there are some parts I’m mixed up about. Like what to do with leftover people.”

“Leftover people?”

Andy put down his backpack and pulled out the notes he’d made from Tiffany’s chart. “Here,” he said. “You start with yourself. Then you go to your parents, and their parents, and keep going as far back as you can. But most of those people have other children. So what about all the brothers and sisters along the way and the people they marry and their kids? What do you do with them?”

“You include them, of course,” she said.

Andy grimaced. “What if they don’t fit on the paper?”

Miz Minna’s laugh was like a tiny bell. “Their names might fill sheets and sheets of paper.”

“I don’t want to fill sheets and sheets of paper,” Andy said. “I don’t care that much about cousins and cousins of cousins. I only care about the Bonners down through my father.” And Coley Joe, of course, he added to himself.

Miz Minna seemed to relax. She reached out and patted Andy’s hand. “Don’t look so discouraged. If you’re interested only in a direct line from Malcolm John Bonner to you, then that’s all you need to write down.”

She giggled. “How will Miss Winnie feel, being left out?”

“Oh,” Andy said. “I’d better put her in, too.” He smiled. “But that won’t be hard. Miss Winnie didn’t get married or have any children, so there won’t be a lot of names to deal with. Maybe I can squeeze her in with the others on just one page.”

He tucked his notes into his backpack and shrugged his arms into the straps. “Thanks, Miz Minna,” he said, hoping she wouldn’t decide to tell them about the senior citizens’ bulletin board. “I’ve gotta go home now and study for a test.”

“Wait a minute, Andy,” she said, and her little paperlike fingers pressed hard against his arm. “You haven’t told me what else you found in Miss Winnie’s box beside the Bonner family Bible.”

“A lot of papers and letters and stuff and a poetry book,” Andy said. “I told Mom I’d sort through it for Miss Winnie, but I haven’t had time to do it yet.”

“Letters? What kind of letters?”

“Business letters, like to an attorney about buying more acreage. Stuff like that. Boring.”

“If you find anything interesting, I’d like to learn about it. Y’hear?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Andy said.

Andy didn’t mention that everything he had found of interest so far had to do with Coley Joe. And he had no intention of talking about Coley Joe to Miz Minna, who had called Coley Joe a family skeleton in the Bonner closet.

The moment he arrived home, he booted up his dad’s computer. As soon as he was on-line, he went into the genealogy bulletin board section and added another message: “This is Hunter again. I asked if anyone had any information about Coley Joe Bonner. Well, now I’ve got more facts to go on. Coley Joe arrived in El Paso at the beginning of December 1877. On December 14, he wrote that he was going with a friend to San Elizario, hoping to buy cattle. If anyone knows where Coley Joe might have gone after San Elizario, will you please e-mail me?”

He wrote the same message on the Texas bulletin board.

Would he get an answer? It was worth a try.

Andy exited Windows and leaned back in his dad’s chair. He fingered the circular nail as he pictured Coley Joe’s smiling face. If you went to San Elizario, he wondered, did you buy cattle? And if you did, then what happened? Where did you take the cattle? Where did you go?

Andy slowly got up from the chair and made his way to the kitchen. He poured a glass of milk, dumped a half dozen Oreos onto the table, and opened his math book. But he couldn’t concentrate. The problems squiggled on the page like pairs of pesky little black lovebugs.

He locked the back door, jumped off the stoop, fastened his helmet, hopped on his bike, and headed for the cemetery. “I’ve got to talk to Elton and find out what he knows,” he said aloud.

CHAPTER NINE

It took less than twenty minutes to pedal out to the cemetery. Andy was so intent on the questions he’d ask Elton that it didn’t occur to him, until he approached the silent, lonely rows of graves, that he’d forgotten to leave a note for his mother. He hadn’t even thought to ask J.J. to come with him.

Andy hesitated at the open gates, wondering if he should turn back and come another time—with J.J. for company.

“Back so soon?” a voice called. Elton stepped out from the doorway of his caretaker’s house.

Andy removed his helmet, leaned his bike against the wrought-iron fence, and walked into the cemetery. “If you don’t mind, there are a couple of things I’d like to ask you.”

Elton grinned and motioned toward the door. “Come on inside. It’s cooler.”

Once inside Elton’s living room, Andy sat where he had sat before on the lumpy sofa.

“I see you’re wearin’ the Bonner circle again.” Elton nodded toward the thong and nail.

To Andy’s surprise, it was hanging outside his T-shirt, in plain view.

“Want to know which Bonner it belonged to? Find the initials.”

“What initials?” Andy asked. He pulled the thong over his head and studied the nail.

“Look on the nail head itself,” Elton said. “You’ll see some initials scratched in.”

Andy squinted. Just as Elton had said, there were faint scratches. He could make out what looked like a tiny M and then a J and a B.

“Hand it over,” Elton said. “I’ll take a look.”

He studied the nail and smiled. “Looks like you’ve got the old man’s nail. Malcolm John Bonner himself.”

Andy took a sharp breath and reached for the circle. The metal seemed warm against his fingers. “Maybe not,” he murmured, saying the words while hoping he was wrong. “His son had the same name. It might have been his.”

“Nope. His son would have had a Jr. scratched in.”

This circle really had belonged to his great-great-great-great-grandfather! Slowly, respectfully, Andy hung it again around his neck, this time tucking it carefully under his shirt.

“Next question?” Elton said.

“I didn’t ask a question yet,” Andy said.

“You was thinkin’ it. Same thing. I suppose you want to know what the circle means.”

“I think I know. Miss Winnie—my great-aunt—she told me that a circle means ‘unbroken.’ ”

“Right. And these circles stood for an unbroken family circle. They all wore them—all the men in the Bonner family. Way I heard it, they was supposed to wear them forever, but old Malcolm, right there on his deathbed, tore his off. He told everybody he’d always hoped that Coley Joe would come back and return the money. But now it was too late. And then he said he wanted that serpent head carved on his tombstone so they’d all remember.”

Andy shuddered. “How could he hate his son?”

“Wasn’t hate. Just his own twisted kind of justice. Malcolm John felt betrayed.”

“But lots of things could have happened to Coley Joe. Why was Malcolm so sure that his son had stolen the money?”

“I always heard there was proof.”

“What kind of proof?”

“Now you gone past me with your questions. The way the story goes, there was some kind of proof all right, but I never learned what it was. You got to find the answer to that one yourself.”

“How?”

“I done told you once. Ask the dead. William Shakespeare’s dead King Lear gave you one answer, didn’t he?”

“Well, yes, in a way,” Andy answered.

“So find out what the Bonners have got to tell you,” Elton said.

“How?” Andy wailed.

Elton leaned back in his chair and scratched his stomach. “I made the first part pretty easy with my Shakespeare clue! I can’t answer everythin’ for you. Some things, like the big answers, you just gotta figure out for yourself.”

That evening Andy raced through his homework and began to sort out the papers in Miss Winnie’s box. There had been a few bad years, but mostly the Bonner ranch had thrived. Andy found countless bills of sale for livestock and for additional acreage.

You came out here owning nothing but land, he said to Malcolm John, and you made a comfortable life for your family. You can be proud of that.

But Andy pictured Coley Joe’s smiling face and, for a moment, was swept into a dark well of sadness. Why couldn’t you have forgiven your son? he thought. What is this terrible proof that destroyed you?

Andy didn’t expect an answer, in spite of Elton’s insistence that he should question the dead, so he wasn’t disappointed when an answer didn’t come. He sorted papers, fastening them together with rubber bands, until his mother came in to tell him it was time for bed.

Before Andy turned out the light, he sat on the side of his bed, his mouth still minty with the lingering taste of toothpaste. Slowly, he opened the drawer of his nightstand and sighed. Just as he had expected, the poetry book was in the drawer—but it was lying on top of the letters. Hadn’t he put the letters on top? He’d meant to, but he couldn’t remember.

Carefully, deliberately, Andy placed the letters on his nightstand and laid the poetry book on top of them. He pulled the leather thong from around his head and placed the circular nail on top of the book. “No more dreams. No more scary stuff,” he said aloud. “I’ve got school tomorrow. I want to sleep.”

But during the moments when he hung in an unreal haze between drowsiness and sleep, Andy heard Elton’s voice saying once again, “Find out what the Bonners have got to tell you.”

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

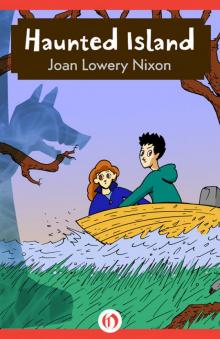

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island