- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

A Place to Belong Page 3

A Place to Belong Read online

Page 3

"School!" Danny's mouth fell open, and he could feel his heart hammering with excitement. "A real school? They told us we'd have schooling, but I—I didn't dare to think about it. Peg and me—we've never been to school before."

"Can you read, Danny?"

"Yes, ma'am. I like to read near as much as Mike does." He glanced down at Peg with concern. "But Peg's young. She never learned."

Peg's chin jutted out, and she made a face at Danny. "Mama said I don't need to know yet. She said that's what school is for, to teach people to read and know their letters and cipher. Bet you don't know all that, Danny."

As it happened, he did, but before he had a chance to answer, Peg went on. "Gussie's going to give me the dinner pail she used to carry. And she's got one for you that used to belong to her cousin who got work laying telegraph lines."

Peg chattered on, but Danny had stopped listening. As he wolfed down his orange along with eggs and biscuits and fried potatoes and ham, he tried to imagine what schooling would be like. He couldn't picture it. He had no idea what to expect.

All day he worked with Alfrid, starting to learn how to care for the horses, hearing with excitement the first splash of milk into the pail as he milked the cows, and walking the boundaries of the farm. But part of his thoughts kept racing ahead to the next day and school.

Finally, Alfrid led Danny to a clearing at the far western boundary of his property. At their feet the ground sloped away steeply. Open fields below them stretched out to the banks of the broad Missouri River.

"This is one of my favorite sights," Alfrid told him. "I like to see the twists and turns of the river. It's like a silver snake."

"It's like a snake with spots," Danny said. "Look at all the boats!"

Alfrid nodded. "There are almost as many boats as on the big Mississippi. You crossed it on your way here. Do you remember?"

"Oh, yes. That I do. We crossed on a ferry, a steam-driven side-wheeler," Danny said. "It was grand! One of the lads—Jim was his name—said he hoped to be chosen by a family who lived in a boat on the river."

"I doubt he'd have much chance for that," Alfrid said.

"That's just what Mike told him," Danny said. "Mike's smart. He always knows what's what."

Alfrid looked down at Danny. "I know that you're a smart boy, too. Has Olga told you that tomorrow you'll be going to school?"

"That she has," Danny said. He took a deep breath. "I want very much to go to school, but ..." He paused, furrowing his brow.

"But what?" Alfrid asked.

Danny tried to find the right words. "Of course, I know that school is for learning, but I don't know how it's done. Peg will be with the little ones, so it will be easy for her, but I don't know where to go, or where to sit, or what I should say. I want to do things the right way and not have other lads thinking I'm stupid."

"I understand," Alfrid said, nodding solemnly. "Fortunately, I can tell you what you need to know." He sat on the grass, and Danny dropped to a spot beside him. "The school is in a one-room building," he began. "Each morning the teacher will ring the school bell, as a sign that school has begun, and all the boys and girls will go into the schoolroom."

"And when I go into the room, where do I sit?" Danny asked.

"As to where your desk will be in the schoolroom, I don't know. The teacher will have to tell you," Alfrid said. "The girls sit on one side of the room, the boys on the other. The little children are in front, the older children at the back. You'll probably be somewhere between the middle and the back of the room."

Danny nodded. He figured that he could wait until the others were inside and see where the boys sat. "What should I do with my dinner pail?"

"There's a section of the room at the back that's called the cloakroom," Alfrid explained. 'There are plenty of hooks where the boys and girls hang their coats, and there are shelves for the dinner pails." Danny nodded again, and Alfrid went on. "There's a stove in the center of the schoolroom, and desks around it. When this new school was opened a few years ago, each student had a desk, but now there are more families in the area, so I

understand that many of the children have to share desks."

"You said the boys sit together, so at least I won't have to share a desk with any girl."

"Anything else?" Alfrid asked seriously.

"What's the teacher like? When I think about him, I imagine someone very important and smart who looks like Abraham Lincoln."

The corners of Alfrid's mouth twitched. "Miss Abigail Clark wouldn't appreciate being compared in looks with Abraham Lincoln," he said. "Miss Clark is a young woman who came from Illinois last year to take the position. She's well spoken of."

Danny sighed with relief. He'd been worried about that impressive teacher.

"Oh, yes. One more thing," Alfrid added. "Behind the school building there are two privies, one for boys and one for girls, and they're clearly marked."

"Ah," Danny said. He'd been too shy to ask, but this was exactly the kind of information that was good to know ahead of time.

"I think we've covered the situation nicely." Alfrid climbed to his feet. "I can't foresee any problems for you."

Danny was satisfied. He couldn't foresee any problems either. He couldn't wait until the next morning, when he'd be able to see it all for himself.

Since the school was only a mile and a half from the Swensons' home, Danny and Peg could walk there and back each day, but Alfrid escorted them on this first trip to show them the way. Peg's legs were short, so the walk took longer than Alfrid had anticipated, and when they arrived at the school yard, it was empty.

Danny could hear a murmur of voices reciting something in unison. "Will you go inside with us?" he asked Alfrid. Danny's palms were damp, his stomach hurt, and he wished that he didn't have to leave Alfrid. He wished that no one had ever thought of sending him to school.

"It will be better for you if I don't," Alfrid said. "You can show the other boys that you can stand on your own two feet."

As Alfrid turned and walked back down the road, Danny gulped, fighting down the fear that rose in a lump inside his throat. He wouldn't be sick. No! He couldn't be.

"Danny, are you scared?" Peg asked.

"No!" Danny snapped.

"Mama told me not to be scared," Peg said. "Mama told me that on my very first day at school I'd make a new friend. She told me I'd have lots of friends."

"Peg! Will you be quiet!" Danny felt close to tears. All the answers he'd gotten from Alfrid were useless against the awful panic he was feeling.

It was better to get this over with as soon as possible, Danny decided. They couldn't stay out here forever. He grabbed Peg's hand and strode toward the building.

"Danny, wait!" Peg wailed so loudly that Danny was sure everyone inside the schoolhouse had heard her.

Danny didn't pause. "Come on, Peg. We're late already!" he snapped.

The door opened with a loud creak and twenty or so students turned to stare.

The teacher, a young woman whose rosy face was framed with a coil of dark hair, smiled at Danny and Peg. "Please come in," she said. "Are you new students?"

"Yes, ma'am," Danny said.

Peg tugged at Danny's arm, and he struggled to keep his balance. "Danny!" she whispered loudly.

"I'm Miss Clark," the teacher said. "And what are your names?"

"I'm Danny Kelly, and this is my little sister, Peg," Danny said as Peg jerked on his arm again.

Miss Clark's forehead wrinkled as she thought. "I don't know of a Kelly family nearby," she said. "Where do you live?"

"Danny! Listen to me!" Peg insisted loudly.

Some of the boys were leaning from their desks to stare at him. A girl about his own age tossed back her curls and snickered.

"Be quiet," Danny growled at Peg. He hadn't thought about how he'd explain who they were. He tried to

speak up but had to clear his throat and start again. "Our family's not here," he told Miss Clark. "Peg and I are living with—that

is, we were adopted by— No, that's not exactly right." He took a deep breath. "We came west from New York City, and Mr. and Mrs. Swenson took us in."

"Oh!" Miss Clark beamed at them. "You're children from the orphan train!"

"Danny!" Peg pulled on his arm so hard that he lost his grip on his dinner pail, and it clattered to the floor. "I have to find the privy!" she shouted. "Right now!"

Some of the children broke into laughter, and Danny's face grew hot. But Miss Clark immediately pointed at one of the older girls and said, "Elsie, will you please take Peg to the privy? Peg, when you return you can sit in this front-row desk with Molly. Danny, please put your dinner pail and your sister's dinner pail and your coat back in the cloakroom. Then you can share a desk with Wilmer Jobes. Wilmer, raise your hand so that Danny can see who you are."

A boy raised his hand slowly and squinted at Danny. Wilmer had a thick shock of straight, tan-colored hair, a long, thin nose, and dark eyes set close together. Danny estimated that Wilmer and he were about the same size and probably about the same age. FU have to watch out for that one, Danny decided.

Danny hung up his coat, and as he was approaching the desk, Wilmer suddenly thrust out a leg. But Danny was ready for it. Instead of tripping and sprawling in the aisle, as Wilmer obviously had hoped he would, Danny brought down his weight on Wilmer's toes.

Wilmer let out a smothered yelp and slid across the seat, as far from Danny as he could get. Danny sat down, took a deep breath, and looked up to see Miss Clark standing beside him, holding a book. "Do you read?" she asked.

"Yes, ma'am," Danny answered.

"Let's see how well, so I'll know where to place you," she answered. "Will you please turn to the story on page three? While the others are preparing their lessons, you may come to my desk and read to me." She turned to walk back to the front of the room.

Danny fumbled with wooden fingers against pages that seemed to stick together, forgetting for the moment about Wilmer, who took advantage of the situation by giving Danny such a shove that he toppled into the aisle.

Miss Clark turned at the sound of the thump and looked at Danny with surprise. Then she looked at Wilmer. "How did that happen, Wilmer?" she asked.

As Danny scrambled up, he glared at Wilmer, who was gazing at Miss Clark with wide, innocent eyes.

"I dunno," Wilmer said. "Maybe he's just clumsy."

"Danny?" Miss Clark turned to him.

"I guess that's right," Danny said. He muttered to Wilmer from the corner of his mouth, "I'll talk to you later."

"You and who else?" Wilmer whispered.

"Are you ready to read, Danny?" Miss Clark asked. "I'm waiting."

Aware of the impatience that had crept into her voice, Danny hurried to her desk and began to read aloud.

As he finished the story, Miss Clark smiled. "Very good, Danny. Thank you. You'll be with the group reading from the fifth reader. Boys and girls in this group, we'll all turn to page twenty-five, and I'll ask Elsie to read the first paragraph."

During the rest of the morning Danny tried to concentrate on his lessons, but he had to keep part of his attention on Wilmer, ready for whatever his desk mate would try next. To his surprise, however, aside from an occasional jab from a sharp left elbow, Wilmer ignored him.

Danny was surprised when Miss Clark pulled a round watch from her skirt pocket and announced that it was time for the noon meal. "You may eat outdoors today," she said. The students crowded to the cloakroom to get their dinner pails. Wilmer had been first, shooting from his seat as though starting a race. Danny wanted to make sure Peg was all right, and was happy to see her hand in hand with a little girl her size.

Danny was among the last to reach the cloakroom. He reached up for the two dinner pails—his and Peg's—and found only Peg's. But on the floor in the corner, against the wall, lay his dinner pail, the lid off and the contents spilled out. The package of sliced bread and cold meat was torn, and heel marks from heavy boots had stomped the food. Danny knew Wilmer had been responsible and he was furious.

He opened Peg's dinner pail. In addition to the wrapped package of bread and meat, she had an apple and a square of some kind of cake with a browned sugar crust. Fine. Now he knew what to look for.

He put the lid back on Peg's dinner pail just as she came into the cloakroom with her new friend. He handed it to her, picked up his own, along with the mess on the floor, and went outside.

Wilmer was sitting on a log bench with two other boys. When Danny appeared, they stiffened, alert, ready for trouble.

"Well, well, there's the boy from the orphan train, come here all the way from New York," one of them said.

"My pa said them Easterners are all abolitionists," the other boy said. "We don't need their kind in Missouri."

Wilmer simply kept his eyes on Danny and didn't speak.

Danny strolled toward them, smiled, and said, "Mind if I join you lads?" Before any of them could answer, he squeezed in next to Wilmer.

"Hey!" Wilmer spoke up. "Who invited you?"

In one speedy motion Danny reached over, grabbed Wilmer's dinner pail, and opened it. Inside, on top of the food Wilmer had brought, lay Danny's sugar cake and apple. "These are mine, so I'll just put them back where they belong," Danny said. He picked up the cake and apple and popped them into his own dinner pail.

"You can't—" Wilmer began, but Danny interrupted.

"Where did this mess come from?" he asked in mock surprise. "It couldn't be mine. It looks like the kind of slop you'd eat." He picked up the wad of torn and dirty bread and meat and slammed it into Wilmer's pail. He glared at Wilmer and said, "If you ever try anything like that again, I'll feed it to you bite by bite."

"I'd like to see you try it!" Wilmer snarled.

"Oh, would you now?" Danny said. As he put down his dinner pail, the other two boys quickly scurried out of the way.

Wilmer was faster than Danny had anticipated. He kicked Danny's feet out from under him, gave him a shove, and leapt up as Danny fell backward over the log. " 'Bite by bite,' was it?" Wilmer taunted.

Danny had tangled with some dirty fighters in New York City. Now that he knew what to expect, Wilmer's tricks would be nothing new. Danny stood, took off his coat, jumped over the log, and faced Wilmer.

They were evenly matched, Danny decided. Wilmer moved lightly and quickly, however, and Danny could see that kicking was one of his favorite moves. Wilmer had taken off his coat, too, throwing it to one side, and he stood with his right shoulder hunched, his arms up, his hands balled into fists.

Good, Danny thought. The way he's holding his shoulder, I can tell that he's not as good with his fists as he is with his feet.

"What's the matter, orphan boy?" Wilmer taunted. "Are you afraid?"

"I bet he thinks he'll get in trouble with the teacher," one of the other boys said, and laughed.

Danny hadn't given Miss Clark a thought. If he got into trouble—well, in this case he hadn't a choice.

"Maybe we should just shake hands and make up," Wilmer suddenly said. He took a step toward Danny and held out his right hand.

But Danny spied the glint in Wilmer's eyes and was ready. He took a step toward Wilmer as though he believed Wilmer were sincere, but when Wilmer's right foot shot out, Danny easily jumped aside.

With his right fist he clipped Wilmer so hard on the jaw that Wilmer sat down with a thud on the packed ground.

Some of the other children had begun to gather around them. "You're gonna get in trouble if you fight!" a girl warned.

"Want to shake hands now?" Danny asked and held out a hand to Wilmer.

"Yeah," Wilmer said and raised his right hand. "I do. Help me up first."

As Wilmer gripped his hand Danny knew he had made a mistake. Wilmer was strong enough to jerk Danny off his feet. The two of them landed in a heap in the dust.

Pummeling as hard as he could and smarting from the blows he took, Danny rolled over and over on the ground with Wilmer. He heard Peg's voice crying out, "

Leave my brother alone!" and someone else shouting for Miss Clark.

All at once Danny felt himself grabbed by his shirt collar and the waistband of his trousers and hauled roughly to his feet. He was face-to-face with Tom, one of the older boys. Another boy—Charlie—had pulled Wilmer up and to one side. "It's over now. Forget it," Charlie said to the crowd that had gathered.

Tom ordered Danny and Wilmer, "Get yourselves

dusted off before Miss Clark gets out of the privy. Hurry up."

"Who started this?" Charlie asked. "You up to your old tricks, Wilmer?"

"He's an Easterner, an abolitionist," Wilmer said sullenly.

Charlie's eyes narrowed. "What's wrong with that?"

Wilmer looked startled, than wary. "Well, that wasn't exactly why we were fighting. Don't matter. The fight's over," he said.

But Charlie's face was stern, and he remained staring down at Wilmer. "Slavery's wrong," he said, "and fighting for it makes everything worse."

Wilmer stuck out his chin. "Who says so? Just you and your family. My pa says if it comes to war, you'll all be traitors to Missouri!"

"Your pa—" Charlie began, but Tom interrupted.

"Don't get into that now!" he hissed. "Here she comes!"

Danny saw Miss Clark hurrying toward them. He tried to smooth down his hair, tuck his shirt back into his trousers, and look innocent at the same time. He knew he hadn't succeeded when she stopped in front of him and asked, "Were you boys fighting?"

Wilmer shot a look at Danny, then rubbed the toe of one boot in the dust. Danny took a deep breath and said, "You might say we were getting acquainted."

Miss Clark's eyebrows rose. "By rolling around in the dust?"

"It could be that was the best way we could find out what each other is like."

He could see that Miss Clark was struggling to keep a straight face. "We don't allow fighting here at school, Danny."

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

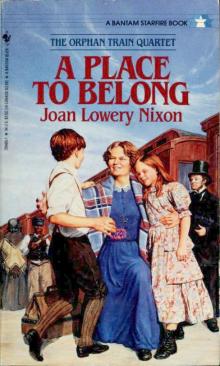

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island