- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

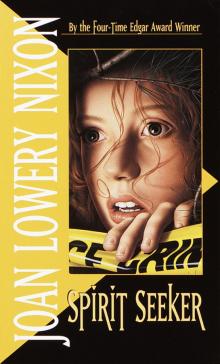

Spirit Seeker Page 3

Spirit Seeker Read online

Page 3

Mr. Arlington’s head swiveled from me to Dad and back again, as if he were a spectator at a tennis match. “You remember me?” he asked Dad, his voice barely a whisper. “I’m the one who found the bodies and called the police. I told that other detective—Mr. Martinez—what I heard and saw.”

“Yes, Mr. Arlington,” Dad said. “We appreciate your help.”

“It’s going to be on the morning TV news.”

Dad glanced at the open gate to the backyard, its torn yellow tape trailing on the driveway. “This is a crime scene, Mr. Arlington,” he said. “It’s off-limits.”

“I didn’t disturb anything.” For a moment Mr. Arlington looked frightened. He suddenly held his watch close to his eyes and said, “I don’t want to miss the early news, so if you don’t need me …”

Without waiting for an answer, he scuttled across the driveway, toward the front door of his house.

In contrast to the Garnetts’ large, beautiful home, Mr. Arlington’s dark brick house was small, plain, and old. Back in the 1980s, when Houston was booming and lots of people had a great deal of money, West University boomed too. One by one the tiny brick homes and their lots were bought for hundreds of thousands of dollars, the houses were demolished, and expensive homes rose in their place. I guess builders expected the entire area to change, but suddenly the oil business cratered, buyers almost disappeared, and many West University blocks were left in a frozen pattern of mansions interspersed with modest bungalows.

The spreading morning light outlined a pickup truck coming down the block, rolled newspapers flying from its windows and slapping the sidewalk. Police cars began to arrive, some marked, some unmarked. Officers in uniform and plainclothes detectives climbed from their cars, some cradling coffee mugs as though they were lifelines. The detectives mumbled greetings to Dad, exchanged brief information, and entered the Garnetts’ house and yard. For a moment my mind went with them into the scene of blood and gore. I shuddered, vividly aware that Dad had to go through this kind of horror over and over.

He turned sharply to look at me, and I realized I’d whimpered.

I wanted to hug Dad, to hold him tightly and pull him away from the horrible specter of violence and death. But, instead, I took a deep breath. “I’m okay,” I lied.

A Channel 2 truck drove up, followed by one from Channel 13. Reporters and camera operators zoomed out like bees from a hive, and soon the sidewalk was covered with a tangle of cables and equipment.

A reporter, microphone in hand, propelled herself toward Dad.

“Go home, Holly,” Dad ordered.

“I can’t, Dad,” I said and begged, as angry tears blurred my vision, “Please don’t make me!”

Dad hates tears and doesn’t know how to handle them. I heard Dad tell Mom once that whenever a suspect broke down and cried, it was hard for him to stay in the room. I know he thinks that Mom and I—so much alike with our red hair and green eyes—are a pair of emotional weaklings, but at that moment I didn’t care.

“Please,” I repeated.

Dad answered gruffly, “You can stay for a while, but don’t get underfoot, and don’t talk to the media.”

Dad didn’t need to worry. The people from the press and television stations, who continued to arrive, weren’t the least bit interested in me. Zeroing in on Dad, they asked, “Are there any new developments? Have you arrested the Garnetts’ son? Is he a suspect?”

I was shocked that Cody was guilty in their minds, simply because he’d survived and his parents hadn’t.

A guy with a camera glanced at me and asked, “Are you anybody?”

I shook my head. I wasn’t the kind of anybody he was looking for. He joined the group surrounding Dad.

Mr. Arlington poked his nose outside his door. He scuttled out to pick up his newspaper, then hurried back inside his house.

The temperature rose rapidly, heat spreading over us like melted butter in a swarmy yellow puddle, so I claimed a patch of deep shade under one of the large oak trees on Mr. Arlington’s front lawn and sat cross-legged on the grass.

Curious neighbors drifted over to watch the action, lining the sidewalk across the street as though they were waiting for a parade to pass by. Two more cop cars arrived, and the officers joined Dad on the driveway, elbowing through the group of reporters. After briefly talking with Dad, one of the officers headed for the Garnetts’ backyard. The others stayed on the lawn, talking to each other. What were they doing? Who or what were they waiting for?

Mr. Arlington came out of his house again and moved in a slow, sidewise gait to where I was sitting. “They showed me on TV, and my name was in the story in The Houston Post. I wish they had left me out of it.” He shook his head sadly and wrapped his arms about his chest as though he was trying to protect himself. “I wish … I wish I hadn’t told them anything,” he said.

“You did the right thing,” I reassured him.

He squatted down and tilted his head, peering at me from the corners of his eyes. “You said if I didn’t tell them all I knew, I’d be helping the murderer.”

I was sure of it! Mr. Arlington did know something that would help Cody! I tried to think carefully before I spoke. It was like approaching a skittish horse. One quick move, and off he’d run.

“If the police catch the murderer, he can’t come back. But as long as they don’t know who the murderer is, he’s out there, and he can murder again.”

Had I gone too far? I held my breath, waiting to see what Mr. Arlington would do next.

His eyeballs darted like swimming fish behind his thick glasses. He frowned in thought, then suddenly got to his feet and strode purposefully toward Dad.

I jumped up and followed.

“Detective Campbell,” Mr. Arlington said, “no matter the consequences, I must explain to you why I was in the Garnetts’ backyard when you arrived this morning.”

This caught a nearby reporter’s attention. He hurried toward Dad, and other reporters, noticing his actions, quickly joined the group.

Mr. Arlington flinched and said to Dad, “Could we talk privately? Without the reporters?”

“Of course,” Dad told him and began to lead the way toward Mr. Arlington’s house.

But Mr. Arlington, struggling to keep up with Dad’s stride, cried, “No! Not in the house! Oh no!”

Dad stopped, surprised, and Mr. Arlington, his face flushing a deep red, stammered, “I—I’m not a good housekeeper, and it—it’s not very tidy. When my wife left me, she took most of the furniture, and … If you could just keep the reporters away, we could talk over there, under the tree.”

Dad waved off a TV cameraman, ordered a reporter to keep her distance, and walked out of their hearing with Mr. Arlington. Naturally, I walked with them. I wasn’t the press. I wasn’t a threat. For the moment I was invisible.

Mr. Arlington gulped loudly, then said, “I wanted to look around the back of the house, in case the police missed something the murderer had left behind. And I wanted to see if there might be bloody fingerprints on the board fence behind the garage. You know, the fence that divides the Garnetts’ yard from mine.”

Dad stiffened. “What fingerprints are you talking about?”

Mr. Arlington held up his hands palms out and waved them like two white flags. “Fingerprints that might have been left on the fence when the murderer climbed over and ran through my yard.”

“You saw the murderer?”

“Yes … well, no. I mean, not exactly.”

Dad bent his head toward Mr. Arlington’s. “Tell me what you saw,” he said.

Mr. Arlington nodded, gulped, and said, “It was so dark I wouldn’t be able to identify him. But he was tall and a well-built, muscular type. He practically flew over the fence between my house and the Garnetts’, then hoisted himself over my back fence.”

“You’re absolutely sure of this?”

Mr. Arlington gulped again and actually shivered, but he didn’t change his story. “I told you, it was dark, and I

couldn’t make out details, but yes … I’m sure I saw someone go over that fence.”

“When did you see him?”

“As I came around the side of my house, crossing the Garnetts’ driveway on my way to knock at their front door.”

“You could see all this from their driveway?”

“Yes. I could see somebody jump over both fences.”

Dad walked with Mr. Arlington to the exact spot and, of course, I did too. Poor Mr. Arlington, who looked more frightened by the minute, was right. It would be possible to see someone climb over both fences.

That meant I was right! Cody was innocent. My heart pounded so loudly I could hear it in my ears.

“Why didn’t you tell me about this sooner?” Dad asked.

“I should have, but I was afraid to,” Mr. Arlington said. “I thought the murderer would come back.” He shivered again as he added, “I still think so, and I’m still afraid, but I want to do what is right.” He pointed at a chubby woman, wearing purple shorts and top, who was standing with a group of onlookers across the street. “There’s Mrs. Rollins,” he said. “She lives in the house behind mine. Maybe she heard or saw something.”

He motioned frantically to Mrs. Rollins, calling her to join them. After a moment of surprise, Mrs. Rollins, and a shorter, younger carbon copy, dropped from the group like a couple of overripe grapes and came toward us.

Mr. Arlington repeated his story and said, “Did you hear anyone in your yard last night? Around nine or so?”

Mrs. Rollins’s daughter poked the center of her chin with an index finger and said, “Was that when Tiger started barking, Mama?”

“That stupid dog’s always barking,” Mrs. Rollins said.

“But last night he was barking different. Remember? You even said a cat must have got in the yard.”

Mrs. Rollins nodded. “I guess I did say that, Trudy, but I don’t remember what time it was.”

“Was your dog loose in the yard?” Dad asked.

“Yeah. Tiger’s more of a house dog, but he’s getting old and he needs to go out often. We leave him outside for a while before we go to bed.”

Trudy grew so excited she bounced up and down on her toes. “So it wasn’t a cat!” she cried out. “Think of that! It was the murderer!” She giggled. “I wonder if Tiger got a taste of him!”

“Tiger bites?”

“Not real bad bites, but he nips if he thinks someone’s an intruder. He tore our plumber’s pants leg, and when the cable TV man came, he—”

The reporters had edged closer and closer, and now their questions piled one on top of another in a confusing jumble, punctuated by Trudy’s squeaks and Mr. Arlington’s loud exclamations.

Dad didn’t try to outshout them. He grabbed one of Mr. Arlington’s arms and led him toward the backyard.

I started to follow them, but just then one of the neighbors across the street shouted, “There he is! There’s Cody!”

He had parked down the street, as close as he could get to his house with the swarm of trucks and cars in the way, and he stood without moving, staring at his house as though what he saw weren’t real but part of a bad dream. As he took in the police tape, he stumbled forward, his eyes frantically searching the crowd. “What’s going on?” he cried out. “Where’s my mom? Where’s Dad?”

Giddy with relief, I shouted Cody’s name and ran toward him, grabbing his shoulders. For a moment he didn’t seem to see me or know me, but finally he focused in on my face long enough to question me. “Holly, where are my parents? What’s happening here?”

Dad stepped up and took charge of the situation. “Please come with me, Cody,” he said, and led Cody around to the side of the house, through the back gate, and into the kitchen. I wasn’t about to get left out, so I followed.

“Sit down, please,” Dad said gently.

Without question, Cody did, staring down at the tabletop as if he were mesmerized. I sat beside him and reached for his hand, holding it tightly. Dad pulled out a chair across from Cody and straddled it.

Briefly, without details, he quietly told Cody that his parents had been murdered.

“Cody,” I whispered, “I’m sorry, I’m terribly sorry.”

Cody wrenched his hand away from mine, dropped his head onto his arms, and sobbed loudly, the way a little kid would cry.

Dad squinted with embarrassment and got up from the table, standing at the sink where he could stare out the window into the backyard, but I put an arm around Cody’s shoulders and held him tightly.

Finally Cody’s sobs became shudders. He shoved back his chair, grabbed a wad of tissues from a box on the counter, and mopped at his face. His face was swollen, red, and blotchy. I wanted to comfort him, but I realized that no one could possibly know how horrible he must feel.

“How did it happen?” Cody asked.

“They were stabbed with a knife.” Dad fixed his gaze on a wall rack that held a graduated set of knives with polished black-and-white bone handles. Cody and I followed Dad’s glance. The third slot from the left was empty, leaving a gap like a lost tooth. “Incidentally,” Dad said, “we haven’t been able to find the missing knife.”

Cody groaned and swayed. I hung on to him, trying to steady him. “When … when did it happen?” Cody asked. “And why? Do you know who did it?”

Dad sat down again and countered with a question of his own. “Are you up to supplying us with some information?”

Cody’s voice grew stronger, even a little belligerent, as he snapped, “You didn’t answer my questions.” He still hadn’t looked at me. He didn’t even look at Dad but kept his gaze firmly on the tabletop.

I told myself that Cody was probably still in shock, yet there was something about the way he was behaving that made me uncomfortable. I believed in his innocence because he was my friend, and after what Mr. Arlington told us, I was positive Cody was innocent. But I had the creepy feeling that Cody was hiding something.

It wasn’t Cody Dad spoke to, it was me. “You may leave now, Holly.”

Cody surprised me by grasping my hand and inching his chair toward mine. “Please let her stay, Mr. Campbell,” he said, and for an instant his voice wavered. “Right now I need a friend.”

His hand was clammy, and fear trembled like an electric shock from his body into mine. “Don’t be afraid,” I told him. I willed him to look at me so he could read the message in my eyes, but again he glanced down at the table.

“Let me stay, at least for a little while,” I begged Dad.

Dad didn’t give me a yes or a no. As though I’d become invisible, he went on to tell Cody everything he’d told Mom and me about the loud music and the complaining neighbor who’d discovered the crime. “That’s all we know at this time,” he said. “We haven’t got the medical examiner’s report yet or the results found by the crime lab.” He paused. “Now, Cody, I’d like to ask you a few preliminary questions. Holly, you may be excused.”

“What kind of questions?” Cody asked.

“Dad!” I complained. “Cody wasn’t even here!”

“Holly!”

“Mr. Arlington told you he saw the murderer. At least he thought he saw a man jump the back fences. Instead of bothering Cody with a lot of questions, why don’t you check out Mr. Arlington’s story?”

“His story—such as it was—will be thoroughly investigated. We’ll look into every angle of this case, which includes getting as much information as I can from Cody.” He paused before he said again, “Holly, you may be excused.”

Dad’s tone of voice told me that I’d pushed him as far as he would go, so with a last squeeze to Cody’s hand, I got up and opened the back door.

“Holly’s right. I wasn’t here when … when it happened,” Cody said. “I left for our lake house around seven-thirty. Mom and Dad were getting ready for some big party they were going to. Everything was fine. No problems.”

Dawdling as much as I could, I slowly closed the kitchen door, unfortunately shutting out the v

oices.

As I walked through the gate to the driveway, where the heat rose in dusty waves from the glaring pavement, I saw Dad’s partner coming toward me. With him was a middle-aged woman dressed in a loose red T-shirt and white shorts. She wore large earrings and a chain around her neck. Both had that shimmery, expensive look of real gold.

Bill Carlin wasn’t as tall as Dad, but he had the same stocky build. About ten years older than Dad, Detective Carlin was missing most of his hair, and his weather-beaten face was deeply creased around the eyes and mouth. He’d been married and divorced three times and liked to say that it was much easier being a bachelor than trying to explain to a wife why his job wasn’t a nine-to-five.

He looked surprised when he saw me. “What are you doin’ here, Holly?”

“Cody Garnett is a friend of mine.”

“I was told that your dad’s talkin’ to him inside the house?”

I gestured toward the back door. “In the kitchen.”

Carlin said to the woman, “If you don’t mind waitin’ a minute out in the yard, Mrs. Marsh, I’ll get my partner.”

They went inside the gate, and I stayed where I was on the other side of the fence, hoping to overhear whatever was going to take place.

Carlin went inside the house, and a few moments later the door opened and shut again and I heard him introducing the woman to Dad.

“Mrs. Marsh is a neighbor directly across the street,” Carlin said. “She has somethin’ to tell us about the time Cody left his house last night.”

Mrs. Marsh hesitated, then said, “I don’t see how it has any bearing on what happened. I mean, Cody had left the house before his parents … Oh, dear! I can’t believe this could happen in our neighborhood.”

“Please, Mrs. Marsh,” Dad said quietly. “Did you see Cody leave his house?”

“Yes, both times.”

I stiffened, not daring to breathe.

“Both times?”

“I was just coming back from taking my dog for a walk when Cody drove off the first time,” Mrs. Marsh said. “It was a few minutes before seven-thirty, I know, because there was a television program on the Arts and Entertainment channel that started at seven-thirty, and I made sure I was home in time to see it.”

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island