- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

Circle of Love Page 3

Circle of Love Read online

Page 3

like a large robin and looked at Frances as though she'd just asked a question.

Frances blushed and said, "Fm sorry. I'm afraid I wasn't listening. I was thinking about my own orphan train ride."

"Of course, dear," Miss Hunter said. She patted Frances's arm. "Mil you visit your former home while you're here?"

"Yes," Frances said. "And there are other places I remember that I'd Uke to see again."

"Good. You'll have this afternoon and most of tomorrow," Miss Hunter said, looking as pleased as if she'd arranged the timing herself.

It was early afternoon by the time Frances had stowed her carpetbag in one of the small bedrooms in the building.

"Perhaps you'll want to rest," Miss Hunter suggested, but Frances shook her head.

"I want to visit my old neighborhood," she said.

"And where is that?"

"West Sixteenth Street," Frances answered, remembering the row of crowded, soot-stained buildings, the constant smell of grease, boiled cabbage, and unwashed bodies.

Miss Hunter bit her lower lip and frowned. After a pause, she said, "Please be careful. There has been an epidemic of cholera in New York, and the authorities believe it festers in the slimis."

Frances was offended. "Where our family lived was a poor area, no doubt about that," she said. "But slums? That's an ugly word. Are they now calling the neighborhood a slum?"

Even though she was embarrassed, Miss Hunter didn't give up. "Oh, dear Miss Kelly, what Fm tiying

to say is, it's not just the cholera I'm concerned about. Please, please arrange to return well before dark."

"I will," Frances said, and smiled. "Don't worry about me, Miss IJimter. IVe long been able to take care of myself."

But Miss Himter didn't smile back. "In the past few years your old neighborhood has been taken over by criminals. Things are different now."

Frances paid uttle attention to Miss Hunter's fears. Hadn't there always been bullies and copper stealers on the streets near her home? And hadn't Mike taught her at an early age how to defend herself? She smiled as she left the Society's ofQces, walking past tidy rows of narrow brownstone houses with steep front steps. Some of them were decorated with pots of red salvia and pink geraniums, the blooms of summer.

She passed dry goods shops, which sold buttons and thread and bolts of cloth, greengrocers' with bins of shiny apples and hard, green pears, and small cubbyholes for dressmakers, confectioners, and barbers.

As she neared West Sixteenth Street, the shops became fewer as tenements crowded together. Here and there Frances saw open doorways and knew that

the people who lived in the small, cramped rooms were trying to catch a bit of fresh air. Occasionally she saw someone sunning in a doorway. She smiled at an elderly man in a threadbare gray suit who chewed on an unlit pipe, and at a woman whose shawl had fallen back from her dark hair.

The man nodded, but the woman threw Frances a look of dark suspicion.

Frances was suddenly self-conscious about her own brown gabardine skirt; high-collared, white cotton blouse; high-buttoned shoes; and dark straw hat Once she had dressed as this woman did, in homespun skirt and shawl, and—unless the weather was cold—her feet had been bare. Memories of her childhood came forth in a jarring jumble of sadness and joy. Frances took deep breaths and walked a little faster.

As her steps led her down West Sixteenth Street toward Ninth Avenue, Frances began to understand what Miss Hunter had been worried about Small knots of children hung around doorsteps or jostled and pushed one another. They darted at some of the adults going past, snatched fist-size chunks of bread from the basket of a helpless old woman, and taunted a bent, arthritic man who walked with a cane. The man struck out in fear, connecting with the nose of one of his tormentors, who ran down the street bawling and bleeding.

Frances hurried to the aid of the elderly man, but he suddenly ducked into one of the tenements. She blinked in surprise as she stared at the poorly constructed building. The wood showed signs of being fairly new, but it was badly stained. Here and there were cracks in the siding that would surely let the cold winter winds blow through, and the windows

were small and grimy. This was the address at which she had lived, but the familiar tenement had disappeared, replaced by an even uglier, more ramshackle building. Frances clutched her reticule with trembling fingers. Where was her home? The people she had known?

A woman stretched out of a lower window and yelled to a group of children, "Go away! Get out of here! Bad boys, the lot of you!"

"Ma'am?" Frances called to her. "Pardon me, ma'am. Do you know what happened to the building that used to be here?"

"Bad fire. Burned to the ground." The woman sneered, and her words snapped with bitterness. "It didn't take the owner long to rebuild. Lost money, he did, until he built something else to cram people into."

Frances felt tears bum her eyes. The building had been cramped and dirty and unsafe, but the room in which the Kellys had lived was a warm and loving part of her life.

But now that room was gone. Her last tie to New York City was no longer here. "Oh, Da. Oh, Danny," she whispered. "How it hurt to lose you! Oh, how I miss you!"

Suddenly the woman in the window yelled loudly, "Tommy! Jimbo! Leave the lady alone or she'll be callin' the police on you!"

Frances felt a tug on her arm. She whirled, swinging her reticule to one side, out of the grasp of a short, dark-haired boy.

He fell against Frances, off balance, and she grabbed his wrist, holding it tightly.

"Let me go, miss!" he yelled. "I did nothin' wrong. I was just passin' by."

"What are you doin* in our part of town, anyway?" one of the other boys demanded of Frances. "Let Tonrniy go!"

Frances looked down into Tommy's dirt-smudged face. "Who is taking care of you, Tommy?" she asked.

"No one. I talce care of myself, I do," he answered.

"You can get help," Frances said. As he struggled to escape, she held his arm and insisted, "Listen to me. Tommy! You don't have to live like this. The Children's Aid Society will send you west to a new home with foster parents to care for you. You'll have good food and go to school and—"

"Go to school?" Someone in the crowd laughed and shouted an obscenity.

Frances looked around, startled at the adults and children who had gathered.

"You and your kind stay out of here!" a man shouted.

"Leave us alone!" a woman yelled. *Think you're better than we are, do you? Come to take our children away?"

The woman in the window leaned so far out she almost fell. "Mind your own business, Sophie!" she screamed. "I seen what happened. Tommy tried to snatch the lady's bag."

"You begrudge the poor lad a few coins? Miss Lade-da's got many more where that come from!" Sophie yeUed back.

"Poor lad, my eyes!" someone said, and laughed. "Best little thief, you mean. Mark my words, he'll be off to prison one of these days."

Soon bystanders were shouting at Frances, at Tommy, and at each other.

Suddenly the sharp shriek of police whistles split the air. Tommy looked up at Frances, and as their

eyes met, she loosened her hold on his wrist. He slipped from her grasp and disappeared into the crowd

A policeman elbowed his way through the crowd of people, many of whom took off in a hurry. He asked Frances, "Were you hurt, miss? Were you robbed?"

"No, Officer," Frances said. "Nothing happened to me. Tm all right."

"No thanks to Tommy O'Hara," the woman in the window called. "He tried to snatch her bag."

"He didn't succeed," Frances said.

"I know the boy. You have witnesses. You could bring charges," the officer said.

Frances thought of her brother Mike, who'd been tempted to become a copper stealer and had been caught. Without the help of Reverend Brace, who had asked the judge to let her brother go west for a second chance, Mike could have been sentenced to time in a prison called the Tombs. If she brought charges against Tommy, mo

st likely he'd be sent to the Tombs. It was doubtful that anyone would come forward to give him another chance.

"I have no intention of bringing charges against the boy," she said.

The officer nodded and wrote something in his notebook. Then he raised his eyes to hers. "Beg pardon, miss, but you don't belong in this part of town. If you'll tell me where you're going, I'll see that you get there safely."

"I'm staying at the Children's Aid Society on Amity Street," Frances said.

"Then I'll walk you there," the officer told her.

Frances snuled at him. "Could you make it Fifth

Avenue instead?" she asked. *There are some places on Fifth that I want to see again."

"Again?"

"I once lived here," Frances said.

For an instant he looked puzzled. Then he returned her smile, apparently reassured by her mention of Fifth Avenue. "To Fifth Avenue it is. My pleasure," he said.

Frances and the officer chatted amiably. As they reached Fifth Avenue and Twenty-second Street, he said, "If you're going to be in New York a few daj^, maybe you'd like to attend the Policemen's benefit picnic supper on Saturday. I'd like to escort you."

Surprised but pleased, Frances smiled. "Thank you," she said, "but I must decline. I'll soon be going home to . . . to . . . Kansas." / almost said 'to Johnny, ' she thought, as a rush of loneUness washed over her.

Frances parted with the officer. Just down the street, near Madison, she looked up at the square gray stone building in which she and Ma used to scrub floors at night

IVs not nearly as large as I remembered it, she thought with surprise. She pictured cranky Mrs. Watts and mean Mr. Lomax, who sent her on errands, threatening to dock her pay if she was even a minute late.

To her surprise, Mr. Lomax suddenly emerged from the building and strode toward her. Frances froze in place, momentarily terrified, just as she had been when she was a child. She'd received nothing from this thin, hawk-faced man but scoldings and recriminations.

But as Mr. Lomax looked up and saw Frances watching him, he tipped his hat and smiled.

"Good afternoon, Mr. Lomax," Frances said quietly. She relaxed, surprised that she no longer hated him. He was a pitiful thing, wrapped inside the shell of his own mean-spiritedness, and he no longer had power over her.

"G-Good afternoon, ma'am," Mr. Lomax stammered. She could feel his puzzled gaze on her back after he had passed her, and she giggled to herself, knowing that he'd wonder all day who she was and how she happened to know his name.

Frances walked up Madison to Twenty-third Street, where trees were thick and green and summer flowers bloomed in well-cared-for beds. Little girls in high-buttoned boots and tucked cotton dresses walked with their mothers or nursemaids in the late-afternoon sunlight, dodging the small boys in matching jackets and pants who darted and raced in games of chase and tag.

Even though it was almost time to return to the Society's building, Frances strolled over to where Fifth Avenue crossed Broadway. It was still an exciting vista of well-dressed women who visited the many shops with their window displays of ribbons, laces, and bolts of material for dresses to be made by skilled dressmakers. Every bit as showy as the window displays were a few wealthy women, wearing large, plumed hats. They rode up and down the avenue in their gleaming open carriages.

Frances remembered with a pang the beautiful doll she had once admired in the window of a nearby store. She crossed Fifth Avenue and stood before the shop's window once again.

The doll in the tucked and pleated pink silk dress was not there, of course, but another doll—equally lovable—was propped in the same spot. It was a baby

doll, with a tiny white bonnet and lace-trimmed christening dress. Its arms were spread wide as though begging to be picked up.

"If only I had a little giri," Frances whispered as she clasped her hancls together. "How I would love to bring her this doll."

But I don% she told herself crisply. Besides, the doll would surely cost a fortune. She tore herself away from the window and headed toward the church her family had attended.

It was cool and silent inside, the heavy stone walls shutting out the noise from the street. Sunlight brightened the stained-glass windows, casting splotches of melting rose and blue and gold on the pews and altar. Votive lights flickered next to the tabernacle and in rows in frx)nt of the shrines at both sides.

Frances genuflected, then slipped into a pew and knelt on the hard wooden kneeler. How often, when she was a child, had she knelt with her family like this on the special occasions when they were able to go to Mass? Just as when she was young, she found comfort in the silence and beauty and love that seemed to swirl around her shoulders like a blanket

She prayed for her family, and as she lit two votive candles she said the special prayer for the dead for Da and Danny. In her mind she could see their happy smiles, their loving faces, which had been so much alike. "1 miss you," she whispered.

The lowering sun cast a final burst of color through the stained-glass windows, then dimmed. Frances hurried to leave, knowing she must return to Amity Street and the Children's Aid Society before dark.

As Frances walked through the front door, Miss Hunter rushed to greet her. She grasped Frances's arms in her eagerness. "Oh, Miss Kelly! We badly need your help!" she cried.

"Where? What has happened?" Frances pulled away from Miss Hunter and reached up to remove the long hatpin that anchored her hat.

"Oh, no, no. It's nothing inunediate. That is . . . it's immediate, but . . ."

Frances waited patiently for Miss Hunter to collect her thoughts. Finally Miss Hunter said, "One of our agents—Mrs. Margaret Dolan—^has become quite ill and is hospitalized."

"I'm sorry. What would you like me to do?" Frances asked.

Miss Hunter took a deep breath and let it out

quickly, her words tumbling with it. "Mrs. Dolan was to escort a group of children to Missouri. Now, of course, she can't, and there is no one else available to take the children, but it's been advertised in three towns when they'd arrive. I know that you're a teacher, and you know how to deal with children, so could you possibly take her place and escort the children on their journey?" Her voice faded to a squeak and she managed to add, "Please, Miss Kelly?"

"When are they scheduled to leave New York City?"

Miss Hunter clapped her hands to her face. *To-morrow morning! I realize that if you take the job it will rob you of a sightseeing day in New York."

Frances suddenly realized that she had no further desire to sightsee in New York. Her happy memories were of another New York City at another time. She'd always have the memories, but it was time to come back to the present—and to the future, which lay in Kansas.

Miss Hunter took another breath, which brought pink back into her cheeks. "There are thirty children. We'll pack some food for them and give you money to buy them milk and bread and whatever else they'll need on the journey. The pay you'll receive for your trouble is not great, but it should meet yoiu* immediate needs." She didn't say "please" again, but her clasped hands and the begging look in her eyes spoke for her.

"I'll be glad to escort them," Frances said, then smiled as Miss Himter sighed with relief. *The ride back, traveling alone, would have been lonely." She didn't speak her thoughts: And it would have given me too miich time to dwell on the argument I had with Johnny.

*Thank you, thank you," Miss Hunter said as she fluttered around Frances. "A cup of tea, that's what you need. Oh! We're having an early supper. Well, there's still time for a cup of tea. And we'll arrange to have you meet the children and get acquainted, of course. Before supper. No, after supper."

Frances took Miss Hunter's hand and led her to a bench just inside the door—the very bench she had perched on, with Mike, Danny, Megan, Peg, and Pete, while they waited for a kind, soft-spoken woman named Mrs. Minton to ready them for their trip west.

"Sit with me for a minute," Frances said. "It will help if I know a little about the child

ren before I meet them."

"Of course! But we'll need the list! I could never remember all their names without a list!" Miss Hunter sailed into the nearest office and back again, waving two sheets of paper as she plopped down on the bench next to Frances.

"Here's the railroad's schedule of stops—some for water and fuel, and some where you can buy fresh milk and bread. Most have privies, too. There will be privies on the train, as well. And here's the list of children. It's alphabetical," she said. "See—^first are Emily Jean Averill, who is four, and her sister, Harriet Jane Averill, who is ten. Oh, how that dear girl worries about her little sister. She won't allow her out of her sight. Goodness knows what might happen if they're separated."

For a moment Frances and Miss Himter stared at each other silently. The rush of pain that came from the memory of being separated from her brothers and sisters was almost too strong for Frances to bear.

She took a deep breath and said, "Please go on, Miss Hunter. Who are the other children?"

'There's the three Babcocks," Miss Hunter said "George Heniy is ten, Earl Stanley is nine, and their baby sister, Nelly Elizabeth, is three." She shook her head. 'TTiey're quiet children and keep to themselves. They're frightened and sorrowed for some reason. It's not the trip west, Fm sure. Tve tried to learn more, but they won't open up to me. Maybe they will to you."

She glanced at the list again. "Nicola Boschetti. She's a lively child. Small for eleven, but happy and healthy. I just hope she'll find a home with a family who'll appreciate her hijinks and not wish they'd chosen a quiet, obedient daughter instead."

Miss Hunter sighed. "Now here's one I worry about Belle Marie Dansing, nine years old. Belle was a foundling, left on a doorstep. She has no known parentage, and she was brought up in orphanages. There's prejudice against foundlings, and it's so unfair."

Frances felt a rush of tenderness toward this child. Had BeUe ever felt a hug or known anyone's love?

Miss Hunter quickly read through the next few names: "Margaret di Capo, eight; Lottie Duncan, eleven; Walter Ray Emerich, five; and Philip Emery, four. They've recently come to the Society, and I don't know them well. It seems that Reverend Brace told me there was some kind of problem with Lottie, but I can't for the life of me remember what it was."

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

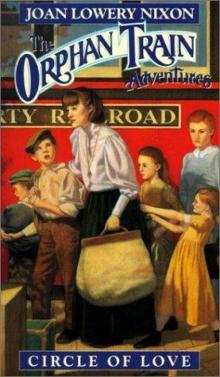

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

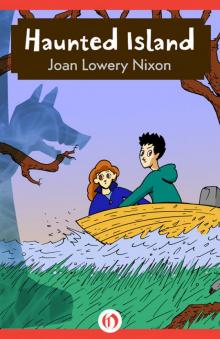

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island