- Home

- Joan Lowery Nixon

Playing for Keeps Page 2

Playing for Keeps Read online

Page 2

“Trust? Mom, I made one little mistake. Can’t you believe it was just a mistake? As for freedom—”

That was when Glory had arrived, making herself at home on the sofa. She’d heard all about the wild party. “There isn’t anyone in west Texas who doesn’t know every detail,” Glory said. “Especially since someone had to call the police.”

She shrugged as she added, “That boy you went to the party with is not the kind you want to date. You want the right kind.”

Mom broke in. Her voice was tight as she said, “It doesn’t matter who was Rose Ann’s date at the party. It only matters that she used very poor judgment.”

Glory gave a more elaborate shrug. “Well, there you have it,” she said. “Poor judgment. Certainly not a punishable offense. Rosie’s suffered enough already. Why don’t we talk about something I have in mind?”

Mom had been trying hard to hide her impatience. “Later, Glory,” she’d said. “If you’ll please excuse us, Rose Ann and I are not through with our family discussion. If you understood—”

“I understand one thing, Linda, which is while we’re sitting here beating a dead horse, we’re running out of time, and that’s what we don’t have much of. Let me borrow Rosie for a week.”

Startled, Mom said, “But you won’t be here. You’re going on that Caribbean cruise with your bridge club.”

That was when Glory told us she wanted to substitute me for her bridge club roommate, who was going to have foot surgery and couldn’t make the cruise. “I’ll take care of expenses. Rosie will be my guest.”

“But you’re leaving tomorrow morning.”

Glory grinned. “Have you ever known me to be unable to do something I wanted to do? Don’t worry. My travel agent’s working on it already. All Rosie will need are her driver’s license and birth certificate, T-shirts and shorts, and a couple of dresses she can wear to dinner. Toss in that cream-colored satin formal she wore to the winter prom. One dinner is formal dress.”

I gasped, trying to take in what Glory was saying as she began giving Mom all the reasons why I should go with her, and explaining that I’d be perfectly safe on the ship while she was playing in the bridge tournament. My heart began to pound. A Caribbean cruise? Tomorrow?

I knew I shouldn’t beg as I turned to Mom, but I couldn’t help it. “I’ve never seen the ocean. I’ve never been out of Texas. I know you’re angry with me, Mom, but please may I go?”

Mom had thought a moment, her face pale and tight. “I can’t let you do this, Glory,” she’d said.

“Who are you punishing, Linda?” Glory had bluntly asked. “Rosie or me?”

I could hear Mom’s sharp intake of breath. Even though I really wanted to go on this cruise, I had to admit that Glory didn’t always play fair.

It had been like this ever since Dad had died when I was fourteen, leaving a stack of medical bills. Glory had paid them and had even paid off the mortgage for the house we lived in. When Mom said my ballet lessons didn’t fit the budget, they were paid for. There was our membership in a swim club Mom couldn’t afford, new dresses for me from Glory’s favorite shops . . . the list was a long one. Mom protested, but Glory always won.

This time was no different. Mom looked at me with her eyes burning, then quickly turned her head and said to Glory, “I’ll have her ready.”

After Glory had left, Mom walked to the end of the room, staring out the windows overlooking the backyard. Her voice dropped, as if she were speaking to herself. “Glory’s once again the fairy god-mother, and I’m the Wicked Witch of the West. She’s won, as usual.”

I backed a step away. “You’re wrong,” I said. “You act like you and Glory are in some kind of contest over me, and you’re not.”

I should have stopped there, but I blurted out, “You blamed me for not being independent and not standing up for what I believe in, but you don’t either. You do what Glory wants you to do. You care what Glory thinks.”

Now I’ve done it, I thought. I’ve ruined everything. I took a deep breath and said to Mom, “I’m sorry about the party, Mom. You’re right. I should have telephoned to ask you to take me home. If I’d known that one of their neighbors would call the police—”

“That’s your only reason?”

“No—no,” I stammered in surprise. “That’s not what I meant.”

“That’s what you said.”

I groaned. “Mom, I don’t want to argue anymore. I said I was sorry. I won’t make the same mistake again. Can’t we let it drop?”

Mom turned from the window and began to walk across the room toward the hallway. “Check your clothes,” she said quietly. “See what needs laundering before you pack.”

I sighed. “Mom, I already apologized. I’m sorry. What else can I say?”

Mom went on as though I hadn’t said a word. “You need a new pair of dress shoes. We can run over to Dillard’s this afternoon and buy them.”

“Okay. Fine,” I answered. Without another word I followed Mom to the doorway. If she wasn’t going to give in, then I wouldn’t either.

A flight attendant rolled her beverage cart to our row and smiled at me. “What would you like to drink?” she asked.

I asked for a Coke, and as I poured it over a cup of ice I made a decision. I’d telephone Mom when we reached the Miami airport. While everyone was waiting for their luggage, I could get away from Glory and talk to Mom in privacy. I began to feel better and the tight place under my ribs slid away. I’d definitely call Mom.

Later, in the airport, while the driver of the cruise ship’s van was collecting our luggage, I found a nearby telephone and made the call, but all I got was Mom’s recorded message. I stared at the phone, disappointed and upset.

“Rosie! Hurry up!” Glory shouted at me.

“It’s me, Mom. I love you,” I said to the machine, and hung up the phone. I ran to join the others, who were climbing into the van.

“Look at that ship! It’s gigantic!” I exclaimed. As the van approached the Miami harbor, the ship loomed over the waterfront buildings.

Mrs. Eloise Fleming, the oldest member of Glory’s bridge club, was squeezed in next to me. She leaned forward, squinting. “What’s gigantic?” she shouted.

Neil Fleming, her seventeen-year-old grandson, who sat across the aisle, tapped her shoulder and said, “You’re looking in the wrong direction, Grandma. The ship’s over there.”

Neil was close to six feet tall, but he sat slightly round-shouldered, as if he were used to hunching over a computer keyboard. His thick hair was dark. In my opinion it was cut and combed all wrong. His eyes, which were a deep blue, looked faded behind the glare of his wire-rimmed glasses. He was wearing a long-sleeved Hawaiian shirt, printed with pink flamingos and red hibiscus. I hoped his grandmother had picked it out.

“Neil knows all there is to know about our ship,” Mrs. Fleming bragged. She adjusted her hearing aid, then said, “Tell us, Neil.”

He didn’t seem bashful or embarrassed. As if on cue, he said, “It’s fourteen decks above water level, four decks below.” He raised his voice until his grandmother nodded that she could hear. “The ship’s length is one thousand and twenty feet, its beam is a little over one hundred and fifty-seven feet, and its gross tonnage is one hundred and forty-two thousand tons.”

“Isn’t he wonderful?” Mrs. Fleming gurgled. “Four-point-plus grade average at school, of course.”

“I know you’re very proud of him,” Glory said. She gave me a knowing look.

I didn’t say a word. I focused on not saying what I was thinking. It was obvious that Glory had known Neil would accompany his grandmother on this trip. It was also obvious that Neil—one of the school’s superbrained geeks in the class ahead of mine, who’d have no use for someone like me—was a guy Glory thought of as the “right kind” of date.

Forget it, I thought, shaken by the sudden realization that Glory’s ideas were no better than Mom’s.

At the thought of my mother I felt anothe

r pang. I resented the fact that Mom hadn’t been forgiving or understanding by the time Glory and I had gotten on the plane. But of course I had to admit that I hadn’t tried to ease the problem between us either.

Frustrated, I pushed the miserable feelings away. I was going on a cruise! It was a time for fun. I might never be able to convince Mom that I could courageously stand up for what I believed in, but I’d do my best to work things out with her later.

Neil broke into my thoughts. “The ship can carry a full load of more than three thousand passengers, and its total crew is one thousand one hundred and eighty.”

Glory was looking at me, so I said the only thing that came into my head. “Wow.”

“What did she say?” Mrs. Fleming asked.

“Wow!” I repeated, this time more loudly.

That seemed to satisfy everyone, including Neil’s grandmother, who began to complain about her ophthalmologist. “At least I can still see the cards,” she said, “and with Neil on hand to push my wheelchair when it’s too far to walk, I should have no problems on this cruise.”

As the van pulled into a parking space next to the boarding area, I leaned against the window, staring at a row of four gleaming cruise ships. I’d be a passenger on the largest ship of all. Since it was spring break, there were bound to be other kids on board. No matter what Glory had in mind about matching me with the “right kind” of boy, it was obvious that Neil wasn’t interested, and neither was I. It was going to be hard enough just finding something we could talk about.

The van came to a stop next to a long, low terminal. With Glory’s carry-on bag in one hand and my own in the other, I climbed from the van and stared up at the ship we’d soon be boarding. “It’s even bigger up close,” I murmured.

“It has two large swimming pools and a theater that’s five decks tall,” Neil said.

“Wow,” I repeated. This time I meant it.

I had to smile as I remembered my telephone conversation with my best friend, Becca, the night before. When she heard I was going on a cruise, she got excited. “Wow! It’ll be like being on the Titanic!” she’d said. She loved that movie so much we’d seen it in the theater eight times and rented it seven.

“Not the Titanic,” I’d answered. “There are no icebergs in the Caribbean.”

“But just the same, you’ll be on a great big, gorgeous ship. Does it have a sweeping staircase?”

“I don’t know.”

“I bet it does. You’re going to look great gliding down the staircase in your formal gown while he watches you adoringly.”

“While who watches me?”

“I don’t know his name,” Becca said, “but you’re bound to meet him—your one true love. You’re going on a glamorous ship with a sweeping staircase, and your name is Rose. It’s fate.”

“I’m too young to meet my one true love,” I said.

“You’re sixteen—almost seventeen. Rose Calvert was only seventeen when she traveled on the Titanic.”

I couldn’t help laughing as she asked, “Are you going to stand in the prow with your arms stretched wide?”

“Oh, sure,” I said. “All by myself.”

“Not by yourself. With him. I want to know every detail when you get back. You’ll tell me everything.”

“I will,” I answered. “I always tell you everything.”

But I didn’t tell her about my argument with Mom. It hurt too much to talk about.

As Neil took his grandmother’s elbow and gently led her to her wheelchair, Glory called from the open doorway of the terminal, “Rosie! Have you got my carry-on?”

I turned so quickly that I collided with a squarely built, muscular man. He staggered a few steps, then caught his balance. “Oh! I’m so sorry,” I said as I realized I’d bumped into a man who was probably somewhere in his late sixties.

“It is quite all right,” the man said, smiling. He politely touched the brim of the straw hat he was wearing, then motioned to a teenage boy who was standing off to one side. “Ricky, venga. Ahora, hijo.”

Ricky, wearing a Cincinnati Reds baseball cap pulled low over his eyes, didn’t respond at first, but as the man snapped “Ricky!” again, the startled boy hurried to his side, grabbed his carry-on bag, and strode with him into the terminal.

Neil pushed his grandmother’s wheelchair to where I was standing. “His face is familiar,” Neil said.

“Ricky’s?” I asked as we entered the terminal, repeating the name I’d just heard. “Maybe you saw him at the airport.”

“No,” Neil said. “The older guy’s. I know I’ve seen his face before.”

I had no answer for him. Eager to enter the ship, I quickly followed Glory and her friends up the long ramp that led to the top of the terminal.

“What’s the bottleneck?” Mrs. Fleming asked as we came to a stop behind a large group of passengers. “Why has everybody stopped here?”

“They’re taking the passengers’ pictures, Grandma,” Neil answered.

With the ship as background through the open window, passengers were posing in groups, smiling or giggling as their pictures were taken by the ship’s photographer. The man I had bumped into earlier, however, was vigorously shaking his head. He propelled Ricky around the group and up the gangway to the ship’s entrance.

“He doesn’t want their picture taken,” Neil said, and I realized he’d been watching them too.

“I understand enough Spanish to know that he called Ricky ‘son,’ “ I told Neil. “But Ricky seems to be only about our age. Do you think he’s really the man’s son?”

“Probably more like his grandson,” Neil said. He quoted some statistics he’d recently read about the number of children and teenagers traveling with grandparents instead of parents, but I wasn’t interested. The last thing in the world I wanted to be was part of a statistic.

I smiled for the camera, cheek to cheek with Glory, then started up the gangway. I would soon set foot on this gigantic, glamorous ship, and I was jumpy with excitement.

Glory fished in her large handbag and pulled out the preboarding papers she’d been given at the airport. As she handed my papers to me, I stepped to one side. At that second someone bumped into me so hard I stumbled backward.

“Lo siento,” the boy named Ricky mumbled. He stopped in his dash down the gangway, reached out, and grabbed my shoulders, keeping me from falling.

“That’s all right,” I told him as I caught my balance. I wondered about the wary, almost fearful look in his eyes. “You were ahead of us. I thought you were already checked in. Aren’t you going the wrong way?”

Ricky shrugged. “Mi chaqueta—my jacket. I forgot,” he said, and began edging away.

The older man took a few steps toward us. “My sister-in-law’s grandson left his jacket on a bench outside the terminal,” he explained. He frowned at Ricky, and I saw the same caution in his expression. “Go. Hurry,” he said in English, and Ricky scurried down the gangway, careful not to collide with anyone else in the crowd of people moving toward the ship.

The man walked back onto the ship, holding up a blue plastic card the size of a credit card. A woman in a trim uniform glanced at the card, then motioned to him to enter.

As I reached the doorway, the woman asked the members of our group for their papers, then gave each of us similar blue plastic cards.

“These cards are your identification, your room key, and your charge card for anything you purchase on the ship,” the woman said. “Always take them with you when you go ashore because they’re your means of returning to the ship after a visit to one of the ports. In fact, keep them with you at all times.”

As I tucked my card into my wallet, I noticed Neil craning his neck to look ahead. “I don’t see him—Ricky’s uncle,” he said. “And I wanted to ask him something.”

“What?” I asked.

“If he ever—oh, there he is.”

Neil hurried to join the man, who was standing at the nearby elevator bank, and I heard him

ask, “Did you ever play professional baseball?”

The man stiffened. For a moment his face was tight with what looked like fear. “What makes you ask a question like that?” he countered.

Neil shrugged. “I’m a baseball fan. I started by getting interested in the game when I was a little kid. Then I began memorizing statistics and collecting photos of the players and teams—you know, getting autographs and baseballs and all that stuff. I read a lot about baseball players. When I saw your nephew wearing that Cincinnati Reds cap—well, it helped me remember. Aren’t you Martín Urbino, who used to play third base for the Reds?”

“No!” The man’s answer was brusque to the point of rudeness, and I looked up, surprised.

As if trying to make up for his attitude, the man began to speak quietly and politely. “You have me confused with someone else, son. I am José Diago, and I have nothing to do with baseball. I operate an imports shop in Boston.”

An elevator door opened and people swarmed inside, Mr. Diago with them. His head was down as though he was afraid of looking anyone in the eye.

Weird, I thought, but then an idea hit me that was even weirder.

2

“HE DIDN’T WAIT FOR HIS NEPHEW TO COME BACK,” I told Neil.

“He didn’t have to,” Neil said. “They both have their card-keys, and we all know our stateroom numbers from the packets that were mailed ahead of time. Ricky can get to his stateroom without any problem.”

“Who was that man, Neil?” Mrs. Fleming shouted. “And who’s coming back?”

“Just somebody I was saying hello to, Grandma,” Neil answered.

For a moment she looked confused, but Glory stepped up, with the rest of the group right behind her. “Have y’all got copies of the list of our stateroom numbers?” Glory asked.

“I think you typed in a mistake,” Dora Duncastle said. “We’re all supposed to be near each other on deck seven, but Eloise and Neil are listed as room thirteen hundred. Isn’t the one in that number supposed to be a seven?”

The Internet Escapade

The Internet Escapade Bait for a Burglar

Bait for a Burglar A Place to Belong

A Place to Belong Nightmare

Nightmare Sabotage on the Set

Sabotage on the Set The Other Side of Dark

The Other Side of Dark Whispers from the Dead

Whispers from the Dead Secret of the Time Capsule

Secret of the Time Capsule A Dangerous Promise

A Dangerous Promise Laugh Till You Cry

Laugh Till You Cry Spirit Seeker

Spirit Seeker The Legend of Deadman's Mine

The Legend of Deadman's Mine Caught in the Act

Caught in the Act Check in to Danger

Check in to Danger Ellis Island: Three Novels

Ellis Island: Three Novels The Name of the Game Was Murder

The Name of the Game Was Murder The Haunting

The Haunting Lucy’s Wish

Lucy’s Wish Playing for Keeps

Playing for Keeps A Family Apart

A Family Apart Nobody's There

Nobody's There Shadowmaker

Shadowmaker Backstage with a Ghost

Backstage with a Ghost The Statue Walks at Night

The Statue Walks at Night Circle of Love

Circle of Love In the Face of Danger

In the Face of Danger Ghost Town

Ghost Town A Candidate for Murder

A Candidate for Murder The Weekend Was Murder

The Weekend Was Murder The Island of Dangerous Dreams

The Island of Dangerous Dreams The Ghosts of Now

The Ghosts of Now The House Has Eyes

The House Has Eyes The Dark and Deadly Pool

The Dark and Deadly Pool Keeping Secrets

Keeping Secrets Secret, Silent Screams

Secret, Silent Screams Beware the Pirate Ghost

Beware the Pirate Ghost Search for the Shadowman

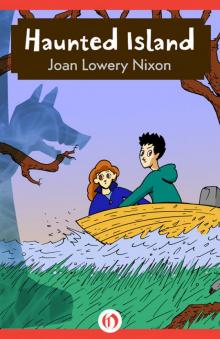

Search for the Shadowman Haunted Island

Haunted Island